STORY BY RICHARD YATES

FOR THE FULL PRINT EDITORIAL VERSION OF THE STORY CLICK HERE

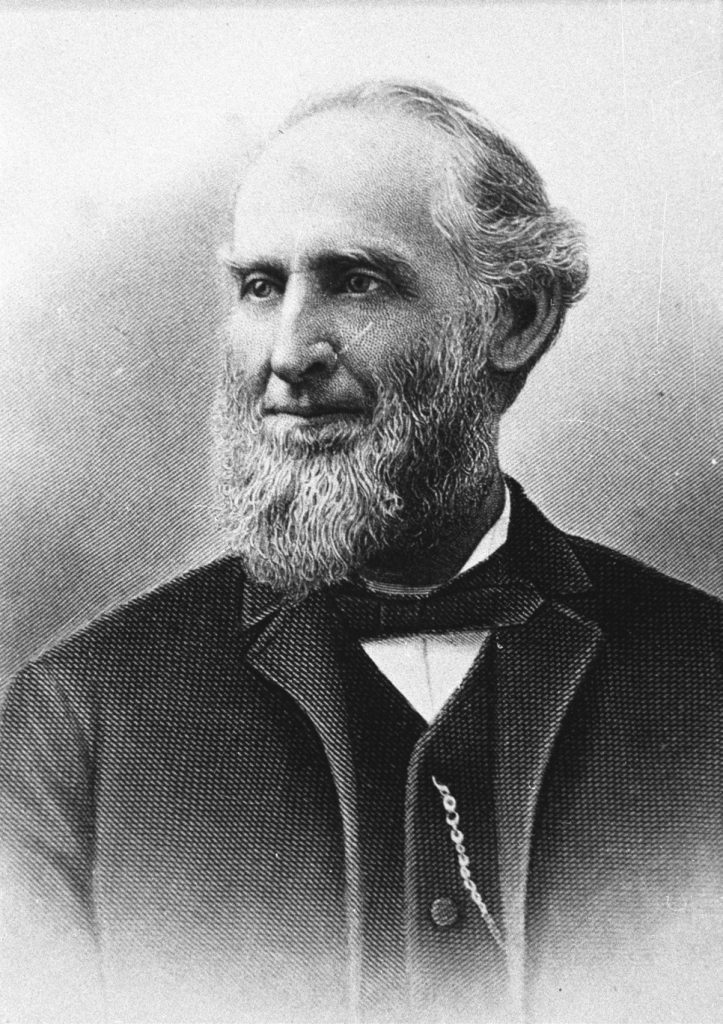

ASA M. SIMPSON, a young apprentice shipbuilder from Maine, came west with his brother during the California gold rush, but Simpson soon realized that few fortunes could be made grubbing for gold.

However, there were opportunities in other areas. San Francisco, a ramshackle boomtown, was in dire need of lumber to handle its expansion. Taking his meager earnings, Simpson purchased a load of lumber from a shipwreck and sold it for a good profit. With this success he realized that the mother lode of riches lay not in the gold fields but in the vast forests of the Oregon coast.

By the mid-1850s, Simpson had lumber mills operating in both Astoria and North Bend. His problem, however, was getting his lumber to market, as the shipping available on the coast was unequal to the task. He quickly determined that Coos Bay would also be an ideal location for a shipyard, which he would build adjacent to his mill. Coos Bay had one of the best harbors on the coast and a bounteous supply of both Douglas fir and Port Orford cedar, which was ideal for shipbuilding because it is impervious to termites and shipworms.

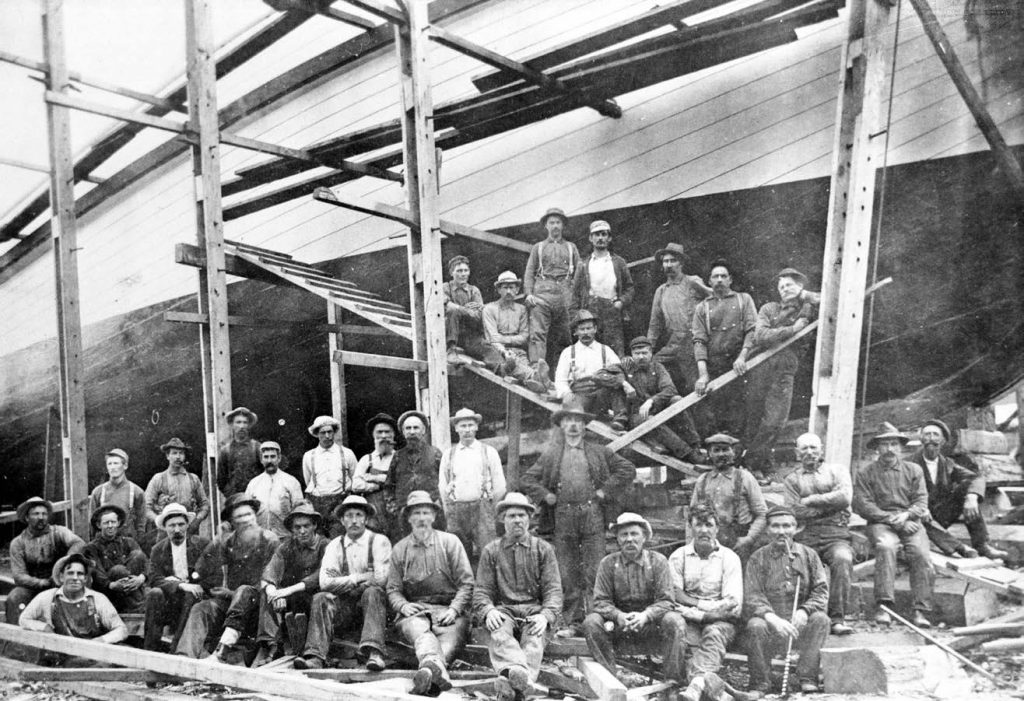

In 1858, Simpson and his brother Robert, both skilled shipbuilders, founded the Coos Bay Shipbuilding Company, the first on the coast north of San Francisco. The Simpsons built ships that were adapted to rocky shores and shallow bays. Built for the lumber, coal, and grain trade, they were tough ships with straight bottoms and shallow drafts. Until its demise in 1903, their shipyard was the most productive on the bay and had constructed more than 50 ships, many of them large, multimasted schooners that were more than 200 feet in length and capable of sailing to ports all over the world.

Did you know that the world’s fastest clipper ship was built in Coos Bay? Neither did we! Turns out Coos Bay had a thriving shipbuilding industry during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

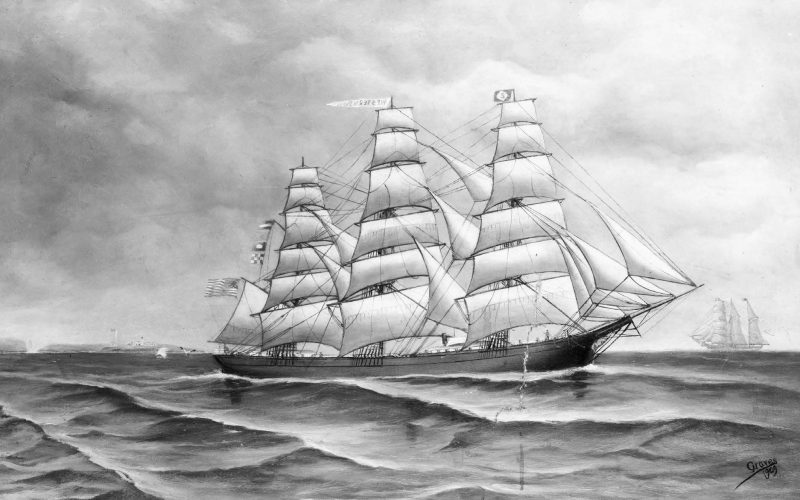

The Simpson yard’s crowning achievement, however, was the construction of the Western Shore, the last clipper ship built in the United States. It came about when Simpson set out to prove that the West Coast could also build a clipper—a fast, three-masted ship with a large sail area—and he and his brother, along with master builder John Kruse, built the largest and fastest clipper—204 feet in length and weighing 1,177 tons—on record. The ship lived up to its promise, breaking records for speed sailing from San Francisco to Liverpool, England.

“It is with pardonable pride that we publish elsewhere that a vessel built in Oregon, the Western Shore, has made the quickest run of the season from San Francisco to Liverpool with a cargo of wheat … that her construc-tion and style of rigging helps to account for the fact that she outstripped the crack sailers of several nations which have left this coast the past season … the fastest of which consumed over 150 days in the voyage, while the Western Shore went past them both with her Oregon colors afloat and moored in the Liverpool docks in 104 days …” —The Morning Oregonian May 15, 1875

Unfortunately, the Western Shore met an untimely end in 1878 when a drunken captain steered it onto Duxbury reef outside of San Francisco Bay, where it sank.

With the closing of the Simpson shipyard in 1903, the largest and most productive shipbuilding operation in the Coos Bay area was that of Knud V. Kruse and Robert Banks—situated in North Bend and operating from 1905–1944. Kruse was an immigrant from Denmark and had studied ship design in Copenhagen. Banks was a shipbuilder from Prince Edward Island, Canada. They first operated their shipyard in Marshfield (later Coos Bay) and later moved to North Bend, locating where the present-day casino is now situated. Over a period of 39 years, they constructed a variety of ships including schooners, steamships, ferries, barges, tugs, fishing boats, and during World War II, eight U.S. Navy minesweepers and five rescue tugs that saw action in the Pacific theater.

In a 2008 article in the Coos Bay World, Mary Banks Granger, daughter of Robert Banks, remembered what the North Bend boatyard was like as a young girl. Crews worked on vessels by day and expanded the shipyards by night, she said. They built three massive sheds so workers could work out of the rain. There were threats during World War I, and fears that ships would be burned, so US soldiers patrolled the yard day and night.

She described that building ships was “like building an old barrel, because everything was a compound curve.” Lumber was dried for up to a year and then the planks were steamed and bent to fit the ship’s curvature. She remembered the smell of pitch and sweet sawdust, the hammering and shift whistles, the ashes that would swirl from sawdust being burned in the wigwam burners.

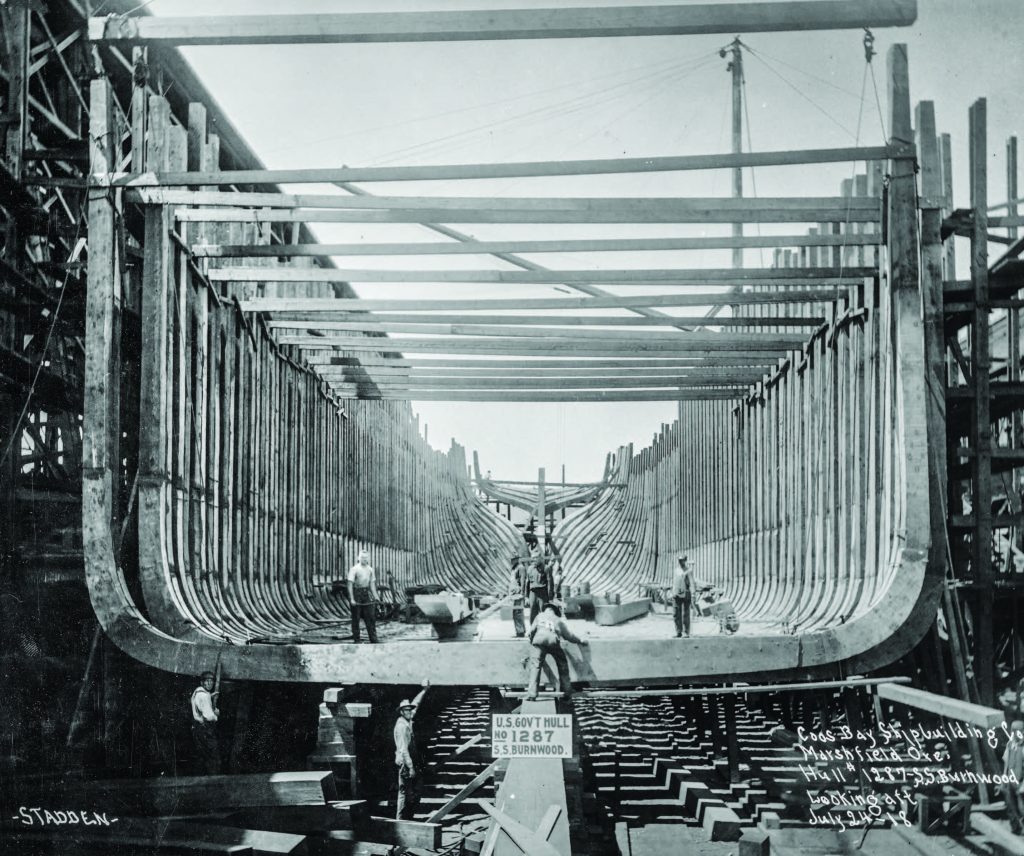

Building a wooden ship began with laying out a number of keel blocks upon which the keel, a long horizontal, rectangular timber sometimes made up of a number of pieces locked together, was placed. Next, “U” shaped ribs were constructed from pieces of steamed wood and bolted to the keel. Planking was then attached to the ribs and interior walls and caulked with oakum, a fiber infused with pine tar. The spars, decking, and rudders were added and the ship was finished by painting and adding the needed machinery. It took a crew of 60 men six to eight months to build a ship.

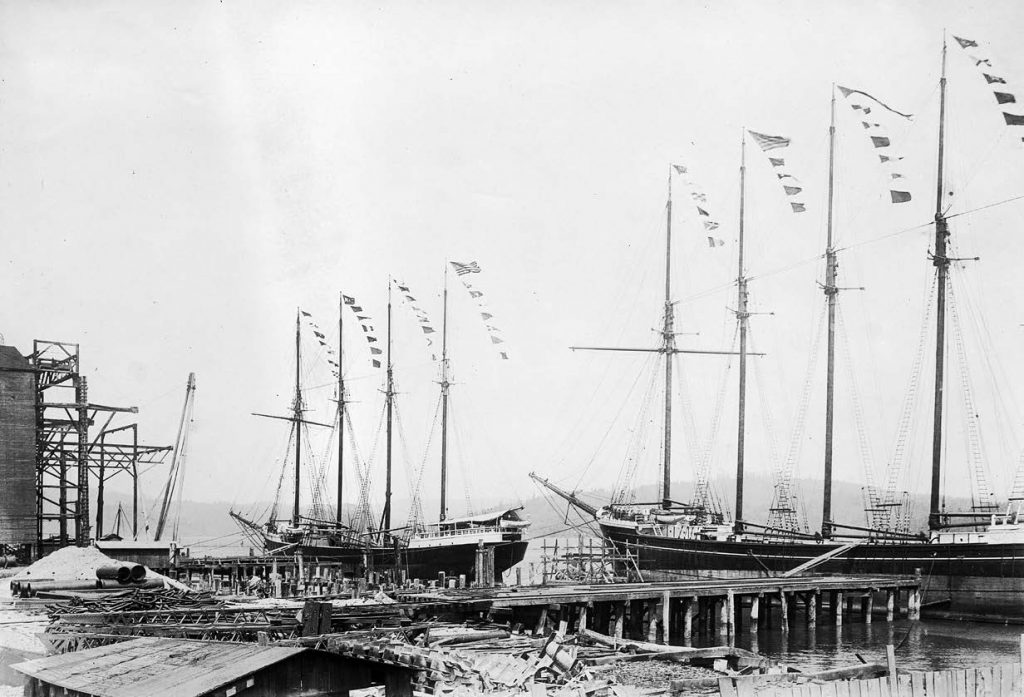

The christening of a new ship, accompanied by speeches and music, was a festive event for North Bend. People came by the hundreds, if not thousands. One ceremony was described in the World by Mary Granger, who when she was 5 years old, christened a steam schooner.

“They had a bottle of champagne that hung from the very top of the bow down. (It was) all tied crisscross with ribbon. It was quite an art wrapping these. My aunt did a lot of it.”

The crowd was always tense, she recalled, as one had to strike the champagne bottle quite hard to break it, and if you missed, it was bad luck.

From 1858 to 1944, there were more than a dozen shipbuilding yards operating in and around the Coos Bay area, many working in conjunction with a lumber mill. In addition to the two already mentioned, the most productive were Henry H. Luse at Empire City and six yards operating at Marshfield, including John Pershbaker, E.B. Dean and Company, Hans Reed, Holland Brothers, and the Emil Heuckendorff. While the industry slowed after WWII, it did not disappear. Jake and William Hillstrom of North Bend built fishing boats and steel tugs from 1940 to 1979, and the Kelley Boat Works built US Navy personnel boats and maintained fishing boats and Coast Guard vessels. Even today, a couple of companies are going strong. Giddings Boatworks of Charleston has been building and repairing fishing boasts since 1979, and Sause Brothers (Southern Oregon Marine) has been building tugs and barges since the 1930s. It’s a heritage to be proud of for this maritime city. ■