STORY BY RICHARD YATES

FEATURED IMAGE BY CRAIG TUTTLE

FOR THE FULL PRINT EDITORIAL VERSION OF THE STORY CLICK HERE

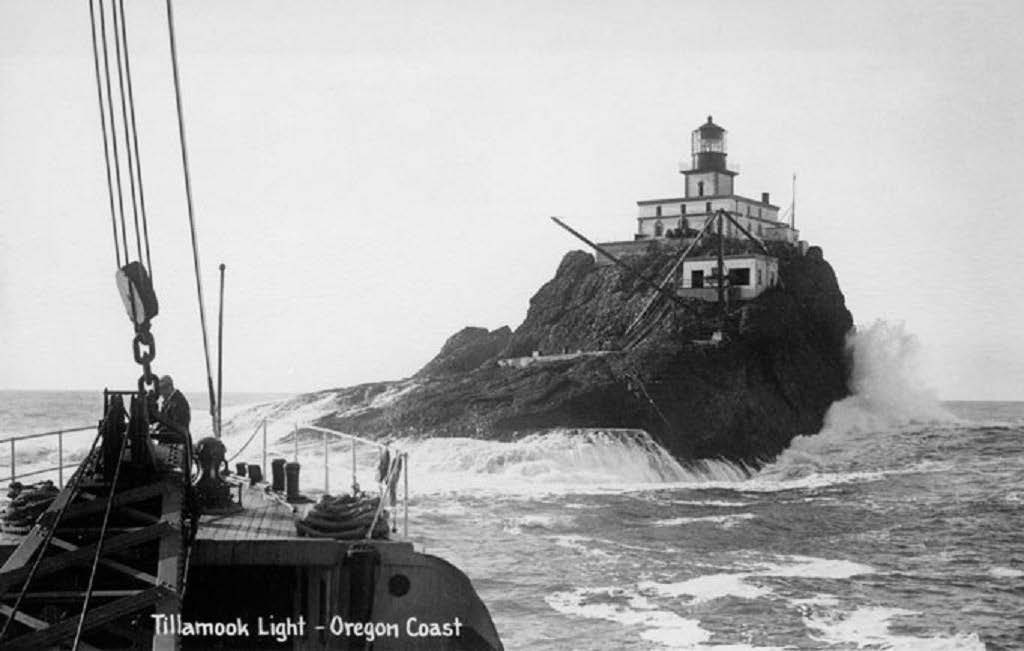

OVER THE YEARS, ships approaching the mouth of the Columbia River along the northern Oregon coast had to run a gauntlet of natural forces that placed them in grave danger. In the winter, they could expect high-velocity winds, crosscurrents, dangerous waves, and the chance of being cast on a rocky shore. The summer added days of disorienting fog.

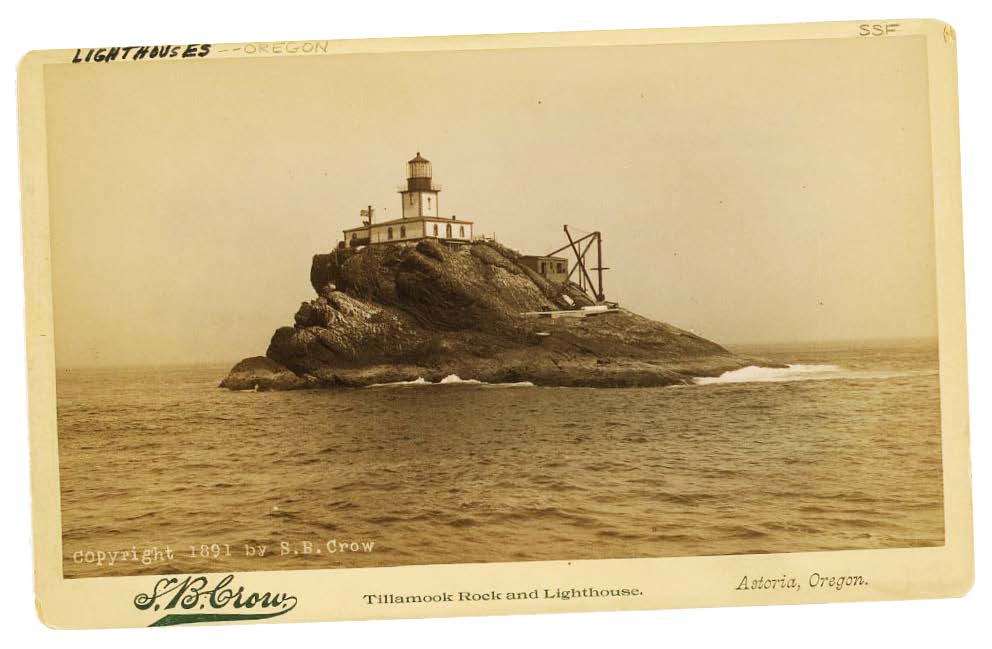

As a result, the approach was a graveyard of shipwrecks. By 1879, the government and local residents believed it was time to add a lighthouse to guide ships along the passage. Tillamook Head, with an elevation of 1,000 feet, was the government’s first choice for its location, but was quickly ruled out because of its summer fog cover, south-facing orientation, and the cost of building a road to the top. The alternative was a basaltic rock—175 feet long and 115 feet high—that stood a mile from shore. Many thought this was a crazy idea, as the rock was pounded by waves and nearly inaccessible. But the government stood firm and efforts to survey the rock were started.

The difficulty of even landing a survey party soon became apparent as swirling water and breaking waves made even a boat’s approach an ordeal. A survey party rowing up in a surfboat finally clawed their way onto the rock but were unable to land any instruments. The surveyor was forced to use a hand tape to make his measurements. Fearing they would be stranded, the men attached themselves to life lines, dived back into the swirling water, and were pulled into the boat. The next attempt was made by a master British light-house builder who was hired to make a construction survey.

On making the leap from a boat and trying to gain a foothold on the rock, he was washed away and his body never found.

The Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, while enduring dangerous, battering storms, guided ships off the Oregon coast for more than 75 years.

News of the difficulties in gaining access to the rock made the recruiting of a construction crew from local workers almost impossible. It was decided to recruit from inland areas where the rock wasn’t known. When this was accomplished, the workers were spirited to Cape Disappointment and away from rumors about the rock’s difficulties until weather conditions improved. Twenty-six days later, a revenue cutter with four quarrymen and their boss anchored off the rock, and after two perilous but successful attempts, made it onto the rock with their tools and blasting powder. Three days later, they were battered and drenched by a fierce storm that soaked their food, clothing, and powder, forcing them to huddle under tattered canvas tarps.

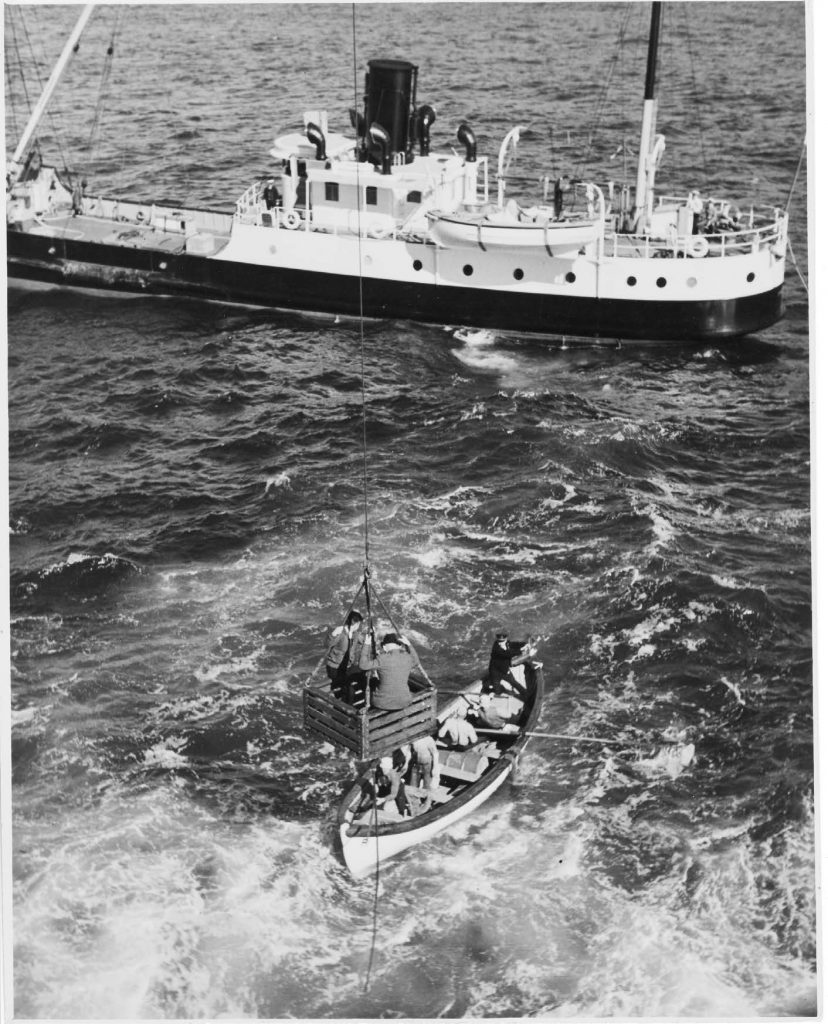

The project superintendent and his aides realized that a dependable means of transporting workers and supplies to the rock had to be worked out. They came up with a clever solution. A large ship was anchored safely away from the dangerous water and a rope was stretched between the ship’s mast and the top of the rock. Using a block and tackle system, a line could be attached with a hook and pulled back and forth to transport tools and supplies. To transport workers, a breaches buoy (a pair of pants that a man could slip into) was attached to the line. It was hugely successful and work to level the rock’s top began.

The first engineering problem to be solved was leveling the convoluted surface of the rock from 120 feet to 91 feet in height. This involved the difficult task of drilling and blasting away the basaltic stone that formed the top of the island. All this was made even more hazardous by waves breaking over the work area, filling drill holes and soaking the explosives.

The living conditions for the workers were miserable at best—consisting of a wind-battered canvas tent with soaked bedding and a cook stove inside. In January 1880, after the crews had been working for four months, a huge storm battered both the rock and workers, and their tools and provisions were swept off to sea. Everyone survived, but it took two weeks for a new supply of food, clothing, and supplies to arrive.

Later, a small frame house was constructed and the crew, now better housed, soldiered on through the winter. By spring, a suitable platform for constructing the lighthouse was completed. The leveling project had taken 224 days to complete, and more than 4,500 cubic yards of rock had been blasted and chipped away.

Using a block and tackle system, a line could be attached with a hook and pulled back and forth to transport tools and supplies

With the site leveled, bids for construction materials were sent out. Government specifications for the materials were very specific, as the project called for the best and the strongest in view of the destructive forces that the lighthouse would be subjected to. Rock was to be the main component, and available supplies of sandstone were bypassed in favor of sturdy basalt obtained from the Mt. Tabor quarry. Fortunately, bricks of the highest quality were easily avail-able as part of the building boom in the Portland area. Sand for mortar was another important ingredient, and it was decreed that it would be sifted to remove any impurities.

Building materials had to be trans-ported from Astoria to the building site, so the changing conditions of the Columbia Bar had to be considered in the choice of transport. It was deemed that a steam-powered vessel, equipped with a large derrick that would enable it to lift quarry rocks, bricks, lime, and sand onto the rock, was best suited.

The most important and second most expensive piece of equipment for the lighthouse was the lantern. A first-order Fresnel lens was ordered at a cost of $8,200, with the stipulation it would be ready to ship from San Francisco by September 1, 1880. In addition to the lantern, a fog warning system was required that would consist of two powerful fog sirens and the boilers to power them.

In the spring of 1880, two derricks to be used for transporting building material were installed on the rock. With good weather and calm seas, construction of the building began, with the cornerstone set on June 22, 1880. It is a testament to the farsighted planning and building specifications of the Light House Board and the skills of its builders that the structure has survived the onslaughts of nature that have beset it for more than 100 years.

After 572 days of labor, The Daily Astorian on January 23, 1881, reported:

“The signaling was a success. The first flash from Tillamook Rock light-house at 7:15 looks gay. Three cheers for the new light, long may it shine.”

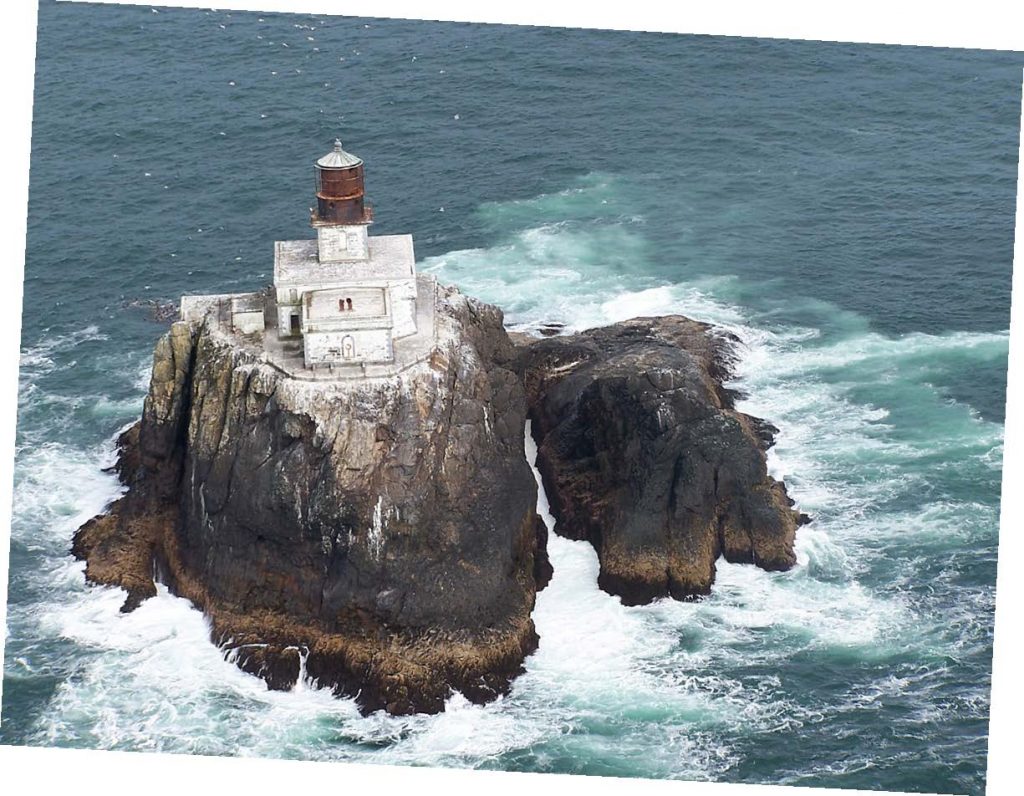

And shine it did. For many years, “Terrible Tilly” was a beacon of guidance. There were, however, interludes of darkness as storms sent damaging waves crashing against the structure. During an 1884 storm, waves inundated the inside of the living quarters as a rock smashed through the roof. The tower windows, the lamp, and the lens also suffered damage. One of the most devastating storms occurred in October 1934. The force of the wind was so strong that the sea washed over the top of the light-house, breaking windows, flooding the inside, and carrying with it rocks, fish, and debris. In the tower, the lamp and lens were also shattered.

With a new aircraft beacon replacing its old lamp, Tillamook Light was operational for another 23 years, until it was shut down by the Coast Guard on September 10, 1957, and replaced with a lighted whistling buoy.

In the 1970s, a General Electric executive bought and repaired the lighthouse to use as a second home. But according to local lore, he spent only one night on the rock and then sold it.

Activity picked up in the 1980s when the lighthouse was purchased by a couple of entrepreneurs who opened the Eternity at Sea Columbarium, a repository for the ashes of the dead. But after about 30 urns were interred there, the facility’s license was revoked in 1999.

Today, the rock is part of the Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge. Access is available only by helicopter, and the rock is off-limits during the seabird nesting season.

Finally abandoned by humans, the rock has reprised its role as the wild, wave-swept home of sea birds and sea lions. ■