STORY BY BONNIE HENDERSON

FOR THE FULL PRINT EDITORIAL VERSION OF THE STORY CLICK HERE

FIRST THERE WERE animals, leaving footsteps in the sand and wearing paths through the dunes and headlands. Then came people—walking the beaches, following the game trails, and forging new trails. Half of those people—the first colonizers, the settlers who followed, all those who made their mark on our coastline—were female. When we beach walk or hike on the Oregon Coast, we’re always walking in their footsteps.

In winter, when you may be the only person on a trail or a stretch of beach, it’s easy to conjure some of those who came before us. Here are five classic hikes on the Oregon Coast inspired by five bold women in history—none of whom had the exquisite winter pleasure of walking in the rain with breathable rain gear or lug-soled shoes.

Five hikes inspired by five bold women who contributed to our rich coastal history:

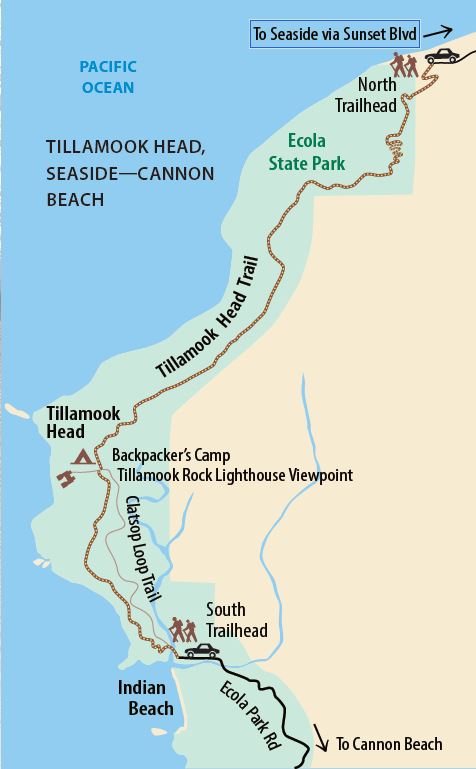

TILLAMOOK HEAD, SEASIDE—CANNON BEACH

6 miles one-way, 990 feet elevation gain

HIKING TILLAMOOK HEAD is not for the faint-hearted, especially in winter. The elevation gain alone is a challenge, as are the roots, the rocks, the sometimes broken-down boardwalks, and the mud. The views, and the sense of accomplishment, are the reward. And it’s got to be much easier than the route Sacagawea followed back in January 1806, when she and other members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition walked from Fort Clatsop to present-day Cannon Beach, hoping to score some blubber from a beached whale. (Sacagawea’s personal agenda, as noted by Captain Lewis, was less pragmatic:

“She observed that she had traveled a long way with us to see the great waters,” he wrote; it would be her first glimpse of the Pacific Ocean, not to mention her first look at such a “monstrous fish.”) Hike it end-to-end with a shuttle car, or go partway up and turn around. An out-and-back hike from Indian Beach to the backpacker’s camp on top of the head makes a nice 2.7-mile roundtrip hike.

South trailhead: Indian Beach parking area, at the end of Ecola Park Road, north of Cannon Beach. North trail-head: South end of Sunset Boulevard, Seaside.

NEAHKAHNIE MOUNTAIN, MANZANITA

2.6-mile roundtrip, 890 feet elevation gain

ON A CLEAR day, the view from the summit knob atop Neahkahnie Mountain is simply stunning; the lower Nehalem Valley and Nehalem Bay stretch out to the south, with seemingly the entire Pacific Ocean visible to the west. You can approach it from the north, but most hikers take the shorter 1.3-mile route from the south. Turn-of-the-19th-century coastal mail carrier Mary Gerritse didn’t have that choice: it was up and over on horseback, all the way from Cannon Beach to Nehalem, then back the way she came. Apparently the route she followed was rougher than the one we hike today, according to her own description; the narrow path along steep cliffs plunging 400 feet to the sea was too much for many men. How did she manage? As Gerritse wrote in her journal, “I did not know how to be afraid.”

To get a better taste of Gerritse’s experience, hike up one side of Neahkahnie and down the other, looping back 1.3 miles along the scenic rock-walled sidewalk bordering US 101 most of the way (5.3 miles total).

South trailhead: Between mileposts 41 and 42 on Hwy 101, turn east at the hiker sign and follow the gravel road 0.5 mile to trailhead. North trail-head: Park at turnout south of milepost 40 on Hwy 101 and cross highway to pick up the trail.

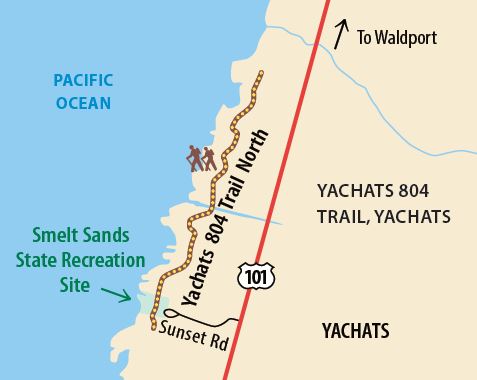

YACHATS 804 TRAIL, YACHATS

1.6 miles round-trip, minimal elevation gain

The 804 trail ends at a beach that stretches nearly to Waldport.

THIS OCEANFRONT PATH leads from Smelt Sands State Recreation Site north to the beach, which stretches nearly 6 miles to Waldport. Annie Miner Peterson must have been intimately familiar with this coastline; as an infant, she was carried here in 1860 by her mother, who was among the Coos Indians forcibly removed from Coos Bay that year and marched to the Alsea Sub-Agency of the Coast/Siletz Reservation in Yachats. Hundreds died in the prison-like conditions here; Annie, who spent most of her childhood at Yachats, and her mother were among the survivors. The Indians were expected to farm, but they also survived by gathering shellfish and, perhaps, netting the smelt that used to spawn in the sand on the rocky shoreline. A walk on the 804 Trail is one way of honoring the generations of Alsea and Coos women and men who have walked here for thousands of years.

Smelt Sands State Recreation Site is west of Hwy 101, 0.5 miles north of Yachats.

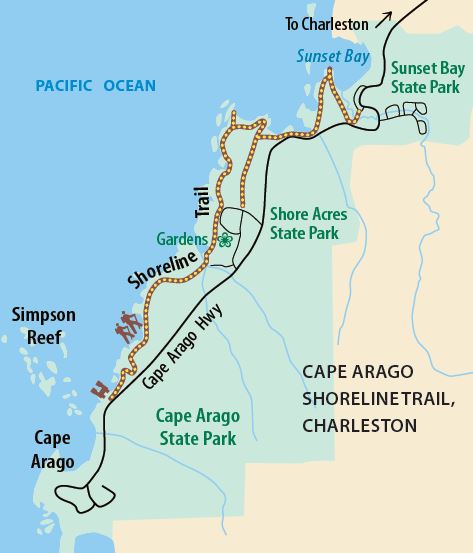

CAPE ARAGO SHORELINE TRAIL, CHARLESTON

3.5 miles one-way, minimal elevation gain

CASSANDRA AND LOUIS Simpson had a torrid romance; at the turn of the 19th century she fled her first husband and child in Hoquiam, Washington, to move with Simpson to Coos Bay, where he founded the city of North Bend and built a mansion surrounded by elaborate formal gardens north of Cape Arago. Their property—including those stunning gardens—ultimately became Shore Acres and Cape Arago state parks. A spectacularly scenic 3.5-mile path links those two parks with a third—Sunset Bay State Park. Walking this path, it’s easy to picture the colorful and adventurous Cassandra Simpson taking in the dramatic coastline from this path, or something near it, though in fact she had an enlarged heart and more likely took in the sights from horseback or carriage. Walk the whole trail round-trip (7 miles), walk it one-way with a shuttle car, or start at either end (or from any of several access points between, including the gardens at Shore Acres) and walk as far as you like, out and back.

Northern trailhead is at the parking area at Sunset Bay State Park (3 miles west of Charleston on Cape Arago Highway). Southern trailhead is at Simpson Reef viewpoint, near the end of Cape Arago Highway.

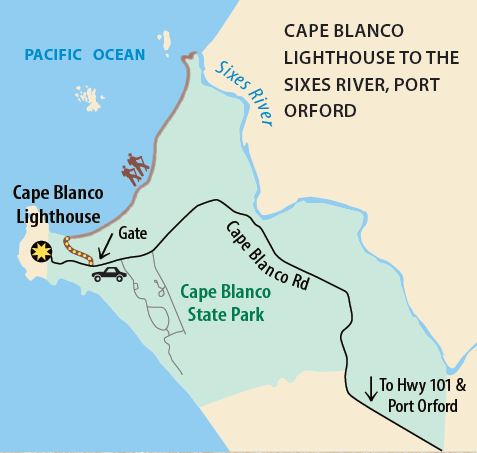

CAPE BLANCO LIGHTHOUSE TO THE SIXES RIVER, PORT ORFORD

3.5 miles round-trip, 200 feet elevation gain

IN MARCH 1903 Mabel Bretherton and her three children, ages 7, 9, and 10, arrived at Cape Blanco Lighthouse, where Bretherton had been hired as an assistant lighthouse keeper. A month earlier her husband—keeper at the Coquille Lighthouse—had died, and the Lighthouse Service saw fit to hire his widow, making her not the first female keeper in the service but the first in Oregon.

Home was a two-story lightkeepers’ house just south of the tower. That’s where the kids would have been on inclement days, but otherwise they were likely outside, exploring the remote headland’s forests, seaside meadows, and beaches. Certainly their mom would have trekked down to the beach when she had the chance, taking a time-out by Mabel Bretherton walking to the mouth of the Sixes River, 1.5 beach miles to the north, and returning with the wind at her back on summer days. You can do the same today; in summer, at low tide, you may be able to wade the river and walk clear to Blacklock Point.

From Hwy 101 between mileposts 296 and 297, take Cape Blanco Highway west 5 miles to the parking area outside the gate across the road to the lighthouse. Walk around the gate and look for the Oregon Coast Trail post signaling the 0.25-mile path down the north side of the head to the beach. | |

Bonnie Henderson is the author of four books, including Day Hiking: Oregon Coast and The Next Tsunami.

BEACH READS

THESE BOOKS REVEAL more about the women in whose steps you’re walking.

- Comin’ In Over the Rock: A Storyteller’s History of Cannon Beach, by Peter Lindsey (2016; available at Cannon Beach Book Company and Cannon Beach History Center & Museum or online at cbhistory.org). Lindsey draws on the journals of Mary Gerritse and other original sources—including interviews with old timers and his own early memories—to bring to life the emergence of what has become an enormously popular tourist town. More information about Mary is also available on the Cannon Beach History Museum blog. (cbhistory.org/blog/articles/mary-gerritse-a-cannon-beach-heroine)

- A Gathering of Finches, by Jane Kirkpatrick (Multnomah: 1997). This scrupulously researched work of historical fiction tracks the life of Cassandra Simpson, someone we would today say made a number of poor life choices. The soap opera of a storyline makes for entertaining chick lit and leaves you not envying her wealth one whit.

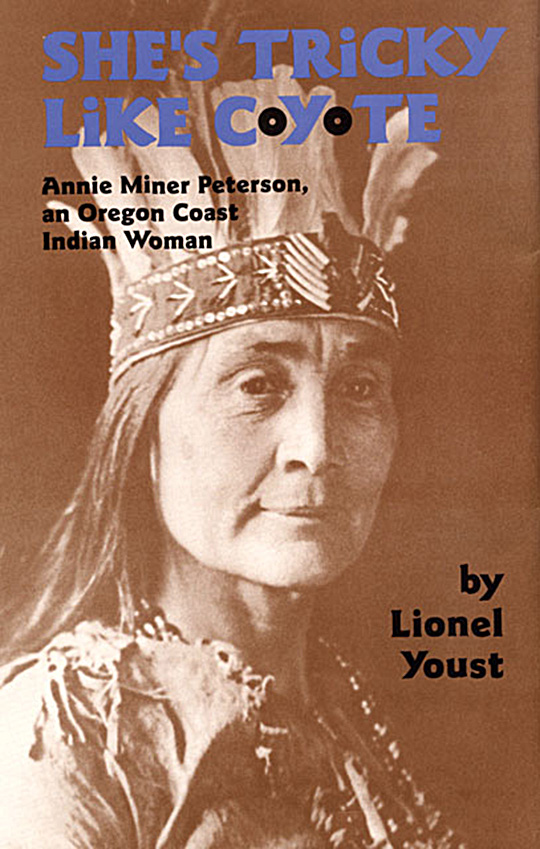

- She’s Tricky Like Coyote: Annie Miner Peterson, an Oregon Coast Indian Woman, by Lionel Youst (University of Oklahoma Press: 1997). In the 1930s, Annie Miner Peterson dictated her life story to pioneering Oregon anthropologist Melville Jacobs; author Youst uses Annie’s first-person account as a starting point for this engaging biography that provides a window into the beginning of the settlement period and the decline—but not the end—of traditional Indian culture and lifeways on the Oregon Coast.

- Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West, by Stephen Ambrose (Simon & Schuster: 1997).There are many accounts of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Sacagawea’s role in it; this one is particularly well researched and a pleasure to read.

- Oregon lighthouse guidebooks offer scant details about Mabel Bretherton’s role as a pioneering female lighthouse keeper; she didn’t keep a journal (that we know of), nor did anyone think to interview her. You can read a few more details about her life and her role in the lighthouse service by searching online. ■