An Astoria teenager helps rebuild and preserve an antique steam locomotive.

STORY BY DAN HAAG

FOR THE FULL PRINT EDITORIAL VERSION OF THE STORY CLICK HERE

IT’S EASY TO assume today’s teenagers spend their time glued to social media or playing video games. But then you meet someone like Ryder Dopp of Astoria and all of those preconceived notions are shown the door.

For the last three years, Dopp, 16, has spent the majority of his Saturdays volunteering in the restoration of a significant piece of Astoria’s history, an antique steam locomotive nick-named the “No. 21 Baldwin.” While the project certainly affords a glimpse into history, it’s also about something equally important: the older generation providing hands-on instruction in skills and techniques that are often viewed as antiquated. It’s hard, tedious, time-consuming work with no definitive finish line in sight.

And Dopp couldn’t be happier.

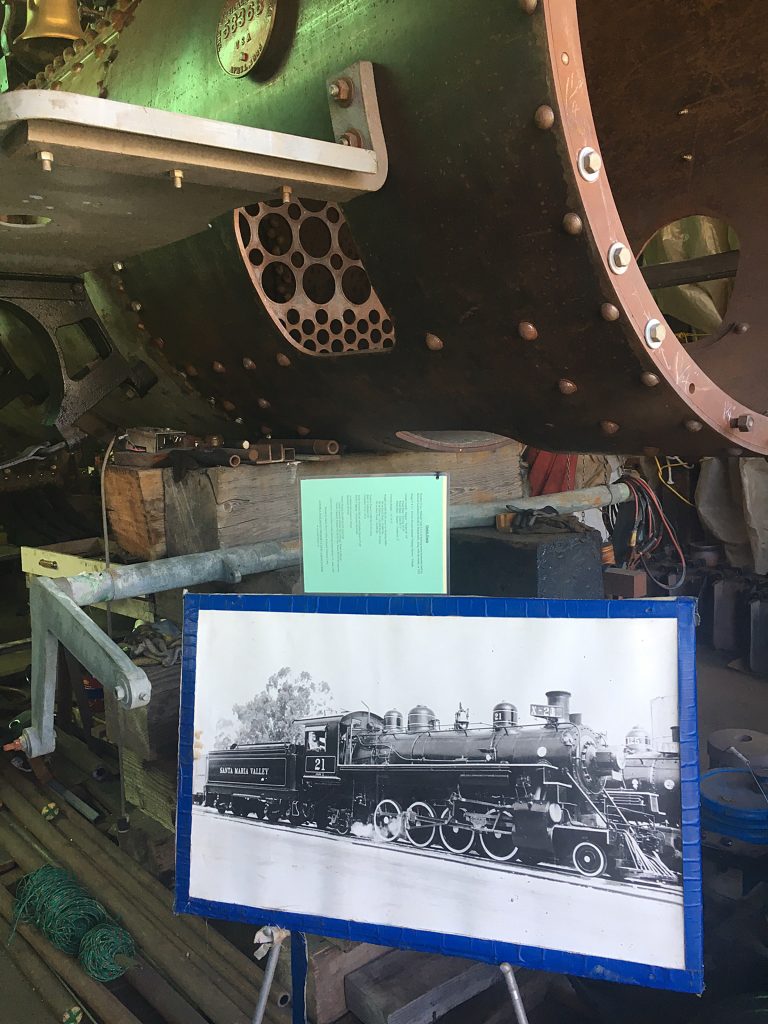

BUILT IN 1925, the No. 21 Baldwin—officially called the Santa Maria Valley No. 21—hauled a variety of cargo for Southern California’s Santa Maria Valley Railroad. No. 21 changed hands a few times over the years, but it was a particular favorite of George Allen Hancock, owner of the large tract of land known as Rancho La Brea, the site of the La Brea Tar Pits.

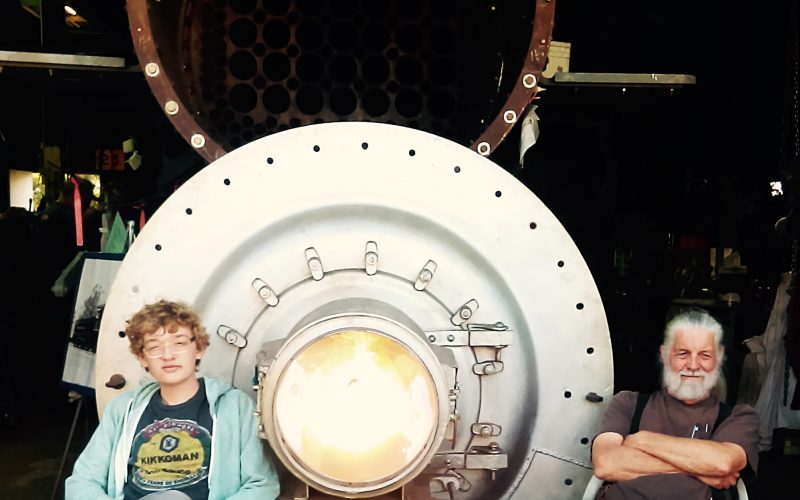

Feature Image: Ryder Dopp, left, takes a break with ARPA volunteer Mark Clemens.

Right: At a recent open house, ARPA displayed historic photos of No. 21. Photo by Dan Haag

Nearly three decades ago, the engine was discovered sitting dormant and neglected in Washington state and eventually ended up in Astoria under the care of the Astoria Railroad Preservation Association (ARPA), a group of volunteers seeking to promote public appreciation of the historical importance of the railroads to Astoria. “A couple of us got together and thought it’d be cool to have a steam train in Astoria,” says John Niemann, ARPA president.

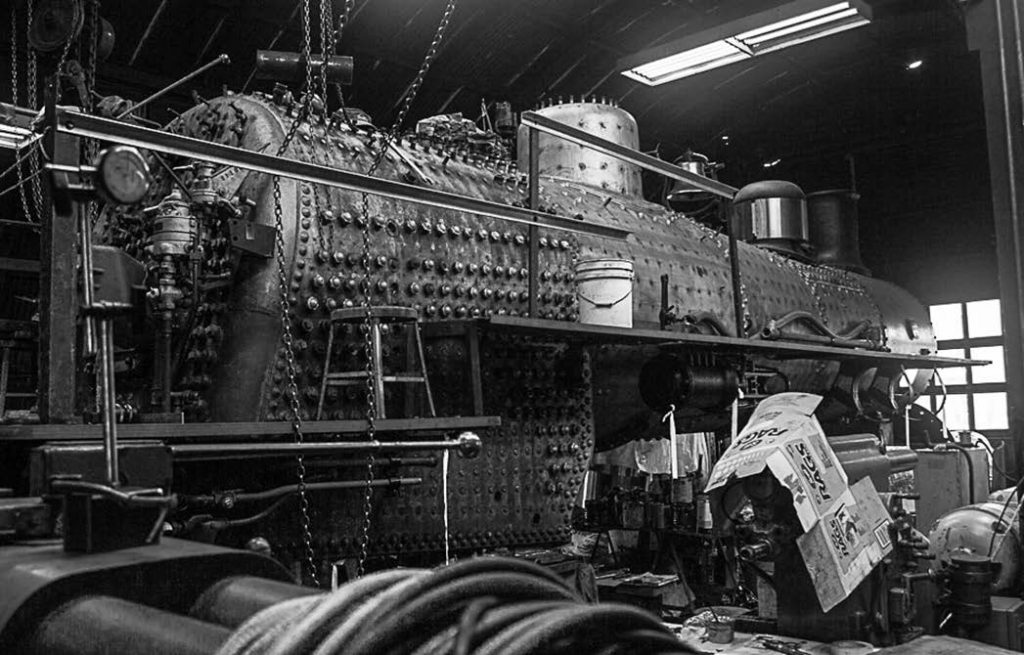

After raising $27,000 in donations to purchase No. 21, ARPA arranged its transportation piece-by-piece to Astoria in 1991. There, it was stripped, cleaned, and painted. The final goal is to restore it to its original working condition and use it as an educational tool, specifically as a tourist excursion railroad along the Columbia River. “It’d pay for future restora-tion projects and help educate the public,” Niemann says, citing examples of successful excursion trains in Portland and nearby Garibaldi.

The restoration has been ongoing since 1998 in the former Bartlett Repair Shop and is painstakingly slow as volunteers strive to accurately restore it to its original condition. Niemann, whose background as a machinist and engineer gives him a wealth of experience to draw upon, thinks the work has its own rewards. “It’s pretty cool they did this stuff in 1925 and we can still learn from it,” he says.

DOPP, WHO SPLITS his time between Astoria High School and home school, wandered into the middle of this Herculean effort three years ago and has since become an integral part of the team.

He’s long had a love of engineering and what he calls “tinkering.” Some of his home-engineering pursuits range from modifying his collection of plastic Nerf guns to teaching himself how to program microprocessors. “I’m con-stantly fooling around with stuff in the basement and going through my dad’s tool box,” he says.

He also professes to a lifetime of interest in trains, everything from Thomas The Tank Engine to wooden trains to elabo-rate electrical locomotive sets. “I really loved laying and rear-ranging the tracks, which always annoyed my friends,” he says.

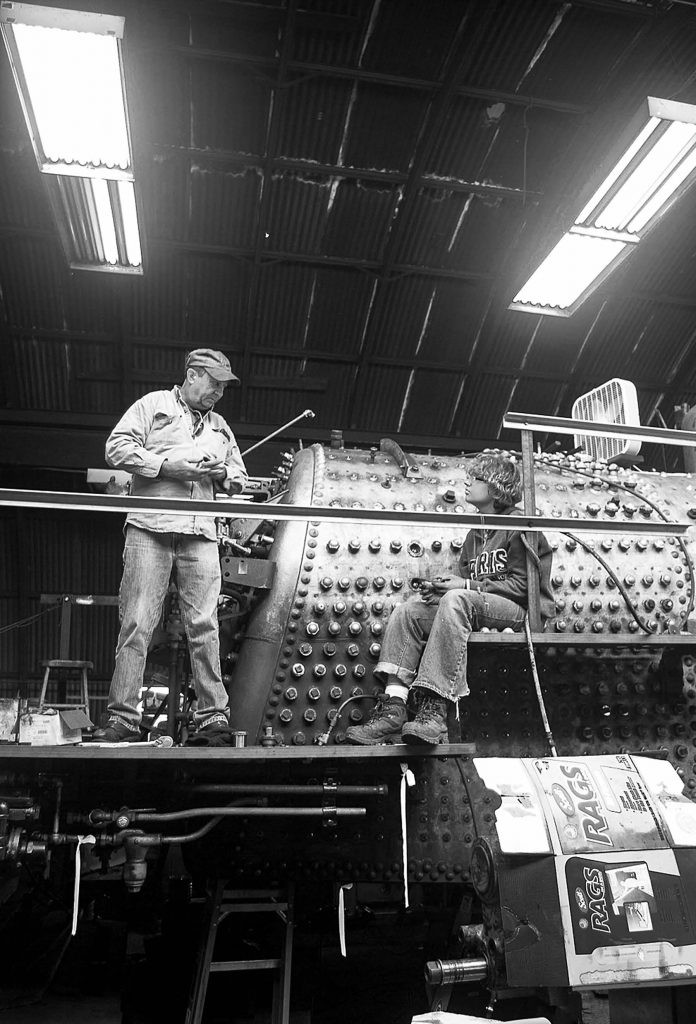

When Dopp’s family moved to Astoria from Portland, their original house was right across the street from the Bartlett shop. Curious after watching the work from afar, Dopp decided to take a closer look. “I just walked over and asked if they needed any help,” he says. Without much in the way of an interview, the volunteer crew put Dopp to work that day. “It wasn’t just like ‘yeah, you can sweep up afterward,’” he says. “They handed me some power tools then and there.”

Niemann says the project is open to the community and all ages are welcome. “We’ll always find something for people to do,” he says, adding that safety is always stressed.

Since that day, Dopp’s eyes have been opened to an entirely different sort of tinkering: laboriously tapping holes for drain valves, adding pins to the locomotive’s crank arm using a hot torch and a jackhammer, and gearing up to place the frame under the body of the locomotive. “I get to do every-thing,” he says proudly.

While Dopp enjoys the responsibility and education the project affords him, most of what he looks forward to when Saturday rolls around is the camaraderie. Talking to the other volunteers—many of whom are old enough to be his grandfather—has its own value.

“They all have such different backgrounds with great stories to share,” he says. “I just like listening to them talk.”

There is no set schedule. Dopp admits that an unwritten rule of the shop is half the time must be spent eating doughnuts and talking, the other half working.

No one knows when the project will be finished. “My first summer, the plan was to put the wheels underneath it. That was also the plan my second summer. And this summer,” Dopp says. “The tongue-in-cheek answer is by 2025 for the 100th anniversary.”

When asked if he’d like to see the work through to the end, Dopp is unsure. He admits he’s busy figuring out what to do with the life that’s ahead of him, like most teenagers. Going to college to study engineering is in the cards, possibly teaching.

Whatever it is, Dopp is thankful for the many doors the No. 21 has opened up for him. “It’s an amazing learning opportunity,” he says. Niemann agrees and hopes the younger generation takes notice. “Ryder just took the bull by the horns,” he says. “Everyone here wishes there were more like him.” ■

FYI

FOR MORE INFORMATION about the Astoria Railroad Preservation Association, No. 21, and how you can help the restoration efforts, contact ARPA. (503-325-5323; astoriarailroad.org)