STORY BY GAIL OBERST

FOR THE FULL PRINT EDITORIAL VERSION OF THE STORY CLICK HERE

I AM SITTING in Coos Bay’s Sunset Memorial Park, between my mother’s and my father’s graves, because this is where my story about sloughs, tidal wetlands, and salt marshes begins.

From this vantage point above the Coos River, where its upper reaches divide into the fingers of Isthmus and Ross sloughs, a flood of memories washes over me; all good. I close my eyes and I am a child again, sitting on the banks of Isthmus Slough with my father and my grandfather. I have just caught some sort of bass. I open my eyes. In the distance, a blue heron rises from the mud of that very slough.

My love of these unique places—where freshwater and tidal saltwater meet—began here on the South Coast. Like any coastal child, I took it all for granted. I thought life would always be this way: mud and clams when the tide was out; ducks and fish when the tide was in. I thought wrong.

Things had been changing long before I arrived. For nearly 150 years, Oregon’s tidal sloughs and saltwater marshes have been drained or dammed or diked by settlers who preferred living and raising crops and cattle on drier land. But luckily, the tide is literally turning. Hundreds of volunteers, agencies, local councils, landowners, and farmers have joined in restoring these precious ecosystems up and down the coast.

Today, you and yours can enjoy tidal or saltwater marshes on public lands in almost every county on the coast. Sometimes they are part of larger national wildlife preserves, or state or federal parks. Sometimes, they are the product of private and public partnerships. Always, these marshes are a benefit to skin, fin, feather, and fur.

I’ve gathered up a short list of places where you can hike, kayak, or just admire the plants and animals indigenous to this unique part of the coast. Most of the places listed are newly accessible to the public, although the grand-daddy of them all, South Slough Reserve, was established in 1974. This is not an exhaustive list; just a few I hope will inspire you to notice them as you drive, hike, or paddle the coast.

ALDER ISLAND MARSH AND MILLPORT SLOUGH

WHERE: Five miles south of Lincoln City, on Hwy 101, just south of Siletz River Road. OPEN: dawn to dusk TRAILS: An easy half-mile graveled loop through the marsh, past the lower Siletz River. WEB: fws.gov/refuge/Siletz_Bay/visit/visitor_activities.html

Most wildlife areas prohibit dogs.

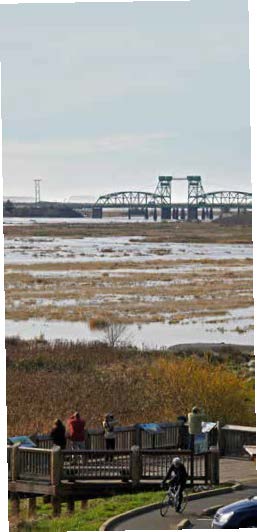

High tide at Alder Island.

The nature trail at Alder Island. – Photos by Gail Oberst

This marsh opened in 2017, and for me, it was an education on a place—visible from Hwy 101—that I had taken for granted. Alder Island’s half-mile nature trail provides rare public access to the Siletz Bay National Wildlife Refuge, a fact already discovered by anglers, who were busily casting into the turbid river when we walked past. The graveled trail takes you past Millport Slough and its tidal marsh, past informational displays, and into the home of many birds. In the winter, you’ll see bufflehead ducks; in the spring and summer, cedar waxwings and sandpipers. While we were there, migrating finches filled the trees with their twitterings. There’s a 3-mile water trail, and a place to launch a kayak or canoe. At high tide, the water fills the channels through the reeds and grasses.

MILLICOMA MARSH

WHERE: Public access is below Millicoma Elementary School, beginning at the public track, in Coos Bay. OPEN: dawn to dusk TRAILS: Park at the track; trail begins under the scoreboard. The longest loop (circling left) is about 1.5 flat miles. A shorter walk, up and back to the observation deck (turning right), is about one-third mile. WEB: coostrails.com/traildescriptions/millicomamarsh/millicomamarsh.htm

This is a great walk for the whole family, during which you are likely to meet locals jogging, walking dogs, and generally sightseeing in any kind of weather. My four-year-old grandniece, Bailey, and I walked the longer loop which leads through the tidal marsh, past the tidal flats, with North Bend and Coos Bay in the scenic distance, and all the ducks, geese, and wildlife you could want. Most of the walk is along a raised dike, which provides great view of the etched channels through the salt marsh. Educational plaques detail the history of Coos Bay’s marshes, reminding us why this town was originally named “Marshfield.”

SOUTH SLOUGH NATIONAL ESTUARINE RESEARCH RESERVE

WHERE: 61907 Seven Devils Road, south of Charleston. OPEN: dawn to dusk; Interpretive Center open Tuesday–Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. TRAILS: There are nearly a dozen trails, loops, and spurs. Best for saltwater marsh viewing is the North Creek Trail (1.5 miles). Combine it with the Railroad Trail (.4 mile) to make a loop back to the Interpretive Center. WEB: southsloughestuary.org

This 5,900-acre slough and estuary reserve extending up into the Seven Devils hills from Charleston includes extensive saltwater marshes. Young and old will enjoy the hands-on exhibits in the Interpretive Center, where you can also pick up a trail map before taking a hike. Informative plaques along the way will give you a great basic training in saltwater “marsh-ology.”

BANDON MARSH REFUGE, NI-LES’TUN MARSH UNIT

OPEN: dawn to dusk BANDON MARSH: From Highway 101 just north of Bandon, turn west onto Riverside Drive and park in the refuge parking lot on the west side of the road. NI-LES’TUN MARSH: From Highway 101 just north of Bandon, turn onto North Bank Lane and drive about a mile to the overlook parking lot on the south side of the road. WEB: fws.gov/refuge/Bandon_Marsh

Because the Bandon Marsh unit is home to clams, crabs, worms, and shrimp, it attracts a multitude of birds. You may see sandpipers, plovers, whimbrels, herons, and falcons from the observation deck. Bring your camera! This area is accessible by foot, stroller, and wheelchair from the parking area.

From the Ni-les’tun parking lot, there is short paved trail into the marsh, which ends at an overlook. From a distance, Ni-les’tun’s flat aspect may seem a bit bland; but look closer. Here is where I first saw the impact of the tides on saltwater marshes clearly outlined on the sides of the incongruous drift-wood. And the birds! From the observation deck, see how many dozens of birds, ducks, and geese you can identify. While I stood reading the interpretive plaques, I was scolded by a screeching hawk-like bird. I was so excited, I dropped my camera. What was it? My curiosity sent me scurrying to contact a birder friend of mine—it was not an osprey or a red-tail, but a northern harrier, otherwise known as a marsh hawk!

WHAT IS A SALT MARSH?

My brother, whose property borders a new marsh that opened in 2017, shrugged his shoulders when I asked him this question and said, “Oh, yeah. The mosquito factory.” He’s not entirely wrong. Bugs love wet places. But so do the grasses, reeds, rushes, fish, amphibians, and birds that eat them—some of which are disappearing from Oregon’s shores as their home environments shrink.

Tidal marshes, also called saltwater marshes, are transition zones between fresh and brackish, or salty water habitats. The channels that wind through these marshy, muddy flats are important sources of food for fish, such as migrating salmon and trout, and serve as nurseries for young fish who aren’t ready for open water. Ebb tides sweep decaying materials from the marsh into the estuary to become part of the food web.

Even as early as 1983, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service noted the importance of these sensitive areas, and compiled a 60-page report on their status in the Northwest (www.nwrc.usgs.gov/techrpt/82-32.pdf). The report names hundreds of plants and animals that thrive in saltwater marshes, from single-celled gastropods to juvenile Chinook, to coots, bitterns, and harriers, and suggests that economic growth may destroy the places that attract people in the first place.

“How can we have maximum economic growth in the coastal zone without destroying the ecological and aesthetic base which inspired that development?” the authors of that report queried.

Thirty-five years later, we may have hit on the answer: Connect people more deeply with these beautiful places by opening them to the public. The new connections have inspired many to preserve what’s left. ■