There is a lot to love about jellyfish—no bones about it.

Image above: Pacific sea nettle. Photo by MacKenna Hainey

Story by Emily Kolkemo

Jellyfish are weird. Anyone who has spent much time on a beach has encountered translucent jelly blobs on the sand, or stumbled upon the clear, marble or oval-shapes of a comb jelly, or come across thousands of blue-tinged Velella velella (by-the-wind-sailors) scattered across the shore.

When my daughters and I discovered a bunch of jellyfish (I later discovered that a group of jellyfish is called a “smack,” which adds to the weirdness) floating around the Charleston marina, we were entranced. We scooped up two into a water bottle, named them Limón and Strawberry, fed them fish food, and watched them swim slowly up and down the bottle. One died, but a week later, Limón was still alive, so we released it back into the bay with the rest of the smack.

As it pulsed out of sight, I was a little sad. Although I had seen many dead jellies on beaches, broken and torn, I wondered where I could see them again—alive. Jellyfish are ephemeral and unpredictable to find in the wild, so the best places to experience the magic of live jellyfish, I discovered, are several aquariums along the Oregon Coast.

Charleston Marine Life Center

Open: Wednesday through Saturday, 11 a.m.–5 p.m.

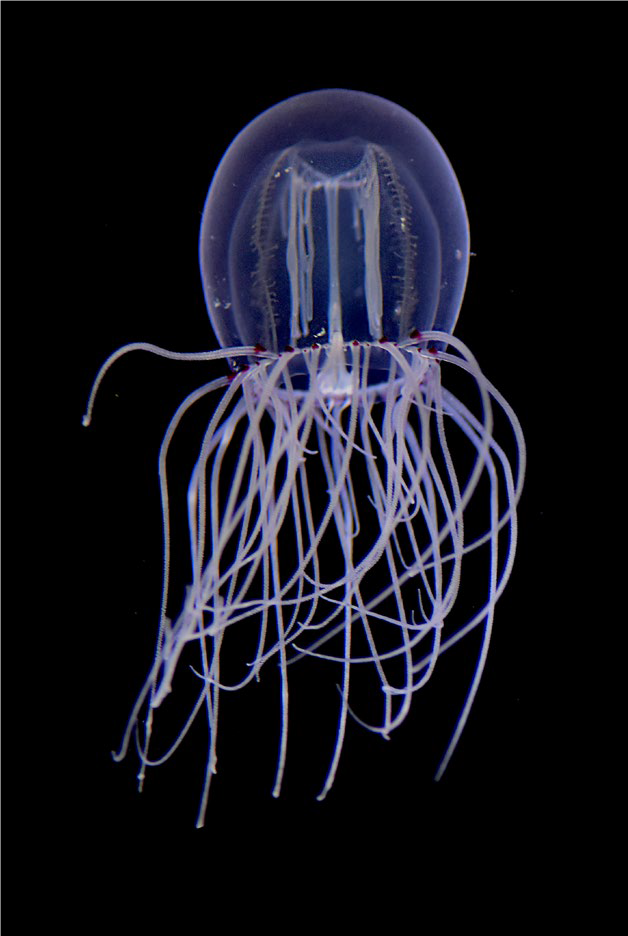

Although the Charleston Marine Life Center (CMLC) does not have a dedicated jelly exhibit, they occasionally have local jellies on display. “Whenever we can, we offer a ‘look what floated past our dock—let’s take a quick look before we put it back in the bay’ opportunity,” says CMLC Director Trish Mace. During the summer and fall, visitors can often find a few red-eyed medusa, a jelly commonly found in the bay, on display. After seeing them, I realized that the “pets” my daughters and I had enjoyed were these jellies.

“This species of jelly is ideal for small, square aquariums as they swim up and sink down in the water column as they feed,” says CMLC educator and aquarist MacKenna Hainey. “The lucky visitors that happen to visit when we do have them on display are always excited to see them up close.”

Periodically, the CMLC has other jellies available for viewing, such as the Pacific sea nettle and the moon jelly. “We only keep this type of jelly on display for a day or two before returning them to the sea,” says Hainey. “These jellies cannot swim well against a current and require a tank with circular waterflow and no corners where they can get stuck.” According to Trish Mace, specialized jelly tanks are something CMLC hopes to install in the future.

“I am struck by their sometimes shimmering, sometimes pulsating, always mesmerizing beauty—all the more remarkable given jellyfish do not have bones, hearts, brains or well-developed eyes,” says Mace. “They are essentially gelatinous bags of water—beautiful, rhythmic bags of water—evoking mystery.” 541-888-2581 x 301; charlestonmarinelifecenter.com

Oregon Coast Aquarium

Open: daily 10 a.m.–5 p.m.

Visitors have long marveled at the translucent moon jellies and orange-colored sea nettles on the main floor of the aquarium—it is a permanent exhibit and one of the best places to see live jellyfish. But the truly adventurous can go on a Sea Jelly Encounter, which is a chance to go behind the scenes and get “hands-on” with moon jellies. Aquarium educator Adam Potter, who led the tour my daughters and I took, says that he prefers the term sea jelly, not jellyfish, because jellies are not fish, after all. The first thing we discover is that jellies are grown at the aquarium, not gathered in the wild. We also learn about the complicated life cycle of moon jellies, who go through several different body forms that don’t look like jellies much at all. But why do jellies sting? “The tentacles, the sting, is to neutralize prey,” says Potter. “Prey can include small shrimp-like creatures, small fish, basically anything that comes within grasp of a tentacle.” But if you get stung by a jelly, don’t take it personally, they don’t really know what they are doing. In fact, the reason you don’t want to touch a dead jelly on the beach is that the nematocysts in their tentacles can sting hours or even days after it has died.

Potter assures my daughters and I that a moon jelly’s stinging cells are weak and typically cannot be felt by humans. Not so with the sea nettle, their sting is akin to a bee sting, so we won’t be touching them. Then Potter takes us to a big tank full of adult moon jellies. The jellies are docile; they seem to react to our touch by pulsing more quickly, but their direction of movement is random. We pet the top of their silky “bells” for a long time. Petting jellies is very relaxing.

The Sea Jelly Encounter is for ages 8 and up; anyone under the age of 16 must be accompanied by a paying adult over 21 years of age. Please reserve in advance by contacting the aquarium.

541-867-FISH; aquarium.org

Seaside Aquarium

Open: Daily at 9 a.m. (closing time varies seasonally)

“Jellyfish are fascinating creatures not only to watch but to learn about,” says Tiffany Boothe, assistant manager and curator at the Seaside Aquarium. “They are made up of 95% water—with a soft, jellylike body and no bones.”

Jellyfish at the Seaside Aquarium are both gathered from the ocean and home-grown. “We are currently raising moon jellies,” says Boothe. “Their polyps are growing in the Aquarium so we collect the newly budded ephyra (larval jellyfish) and grow them up.”

Jellyfish have a peculiar life cycle, starting with an egg, which when fertilized becomes a free-swimming planula, which then settles onto a surface like a rock, a dock, or kelp, and becomes a polyp (sort of resembles a tiny anemone). After a period of time, an ephyra floats off from the polyp and eventually grows into an adult jellyfish. For such simple creatures, it is a very complicated pathway to adulthood. Strangely, some jellyfish can “reanimate” themselves, and these also make good specimens to show visitors.

FYI

To learn more about jellies that are common to the Oregon Coast, download the Oregon Sea Grant publication, Pocket Field Guide: Oregon Jellies. ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/defaults/1g05fh80z

This story appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of Oregon Coast magazine. Unless otherwise notes, photos provided by the Charleston Marine Life Center, Oregon Coast Aquarium, and Seaside Aquarium.