Story by Cheryl D. Wanner

In 1788, Captain Robert Gray sailed his sloop, Lady Washington, into what is now Tillamook Bay and made the first recorded white contact with the indigenous people of the area. Gray wrote of friendly trade between his crew and the local inhabitants which took an ugly turn when one of his men was killed in a squabble over a stolen cutlass. Putting back to sea, he could scarcely have imagined it would take his race just 63 years to dispossess the natives of the lands they’d held from time immemorial.

In 1806, Lewis and Clark recorded trade with the Clatsops near Young’s Bay (Astoria) as well as the neighboring tribe to the south known as the Killamucks (or Killamooks or Killamox). The white settlers who followed would rename these more southerly inhabitants the Tillamooks, perhaps out of misunderstanding or perhaps they found it easier to say. Once thought to mean land of many waters, Tillamook is of Chinook origin and translates as people of the Nekalim (Nehalem) country.

The Tillamook people belong to the Salish language family, each band having its own dialect. Historically, they lived along the coastal strip from Tillamook Head south to Cape Foulweather with villages located on the bays and near the mouths of five major rivers emptying into Tillamook Bay. The principal bands are the Nehalem, the Tillamook proper, the Nestucca, the Neachesna (Salmon River), and the Siletz, though villages also stood on Netarts Bay and at the head of Bayocean Spit.

Despite the cutlass incident at the time of Captain Gray, the traders and settlers who followed early explorers found the Tillamooks to be friendly, welcoming, and eager to exchange goods. Lewis and Clark described them as short with copper-brown skin, black eyes, wide mouths and noses, and crooked legs (the result, most likely, of squatting on their calves and kneeling in their canoes). Their most distinctive feature was the width and flatness of their foreheads, sometimes presenting a straight line from the bridge of the nose to the top of the head.

Head flattening, practiced by many coastal cultures from the central Oregon Coast to Alaska, was considered a mark of beauty and social distinction. Ten days after birth, slight pressure was applied to an infant’s forehead from a padded board attached to the cradle.

The process took eight months to a year to complete, was painless with no mental side effects, and clearly defined who had status in the community and who did not.

Puberty was a highly critical stage in life, ushering in both adulthood and the securing of one’s place in society. Possession of a guardian spirit and subsequent spirit powers were often prerequisites for personal status in a village. Spirit quests, undertaken at puberty, were open to girls as well as boys as was the practice of shamanism, though certain elements of this profession were limited to one sex or the other.

A boy wishing to go on a spirit quest had to be sent out by his father or an elderly member of the village. He would spend three to five days alone in the forest, fasting and bathing in cold streams. The nature of his spirit power would determine his vocation, such as a hunter, fisherman, or canoe builder, or it might gift him with oratory or war leading skills. A girl would leave the village for a single night following the cessation of her first period, but she could not reveal her power until middle age.

Though marriages were sometimes arranged or strongly pressured, young people could choose their own mates. Spouses typically came from other villages within the tribe. The marriage was brokered by an older man, and gifts from the prospective groom were offered to the girl’s family.

Unless death was accidental or occurred in battle, a person was attended by a shaman at time of passing. The body, dressed and wrapped, was housed in the lodge for two to three days, the face painted red as well as the center part of the hair. The body was placed in a canoe on forked poles of differing heights with a second canoe inverted and cinched down over the first. Drainage holes in the lower canoe allowed rainwater to run through, and former possessions, hung on the outside, were damaged to keep the living from using that which had belonged to the dead.

Shamans enjoyed great prestige in the village as did hereditary upper-class families. Leadership, however, appears to have been variable, depending on the needs of the moment and the ability of an individual to organize work parties or solve disputes. On the lower social rungs were those with no spirit powers and (in some villages) slaves taken in raids on other nations. Individual villages were autonomous with no sense of political unity to other bands.

The Tillamook people lived on waterways, so the canoe was their primary means of transportation. Highly skilled carvers hollowed these craft from a single tree, using chisels, hammerstones, mauls, adzes, and fire. Sizes ranged from a small shovelnose capable of holding two to three people to a six-to-twelve-man mid-sized craft to an ocean-going trading or war canoe that accommodated 20 to 30 people.

Fish, particularly salmon and steelhead, along with a variety of shellfish played a significant role in Tillamook diet. Game hunted included deer, elk, beaver, bear, fowl, seals, and sea lions. Berries and wild greens were gathered. Roots, especially those of the camas, were also an important staple.

Because the people were mobile in the summer, seeking game and gathering stores, grass shelters were often erected for short-term use. Actual villages consisted of longhouses built of cedar planks. Some of these were constructed entirely above ground while others were dug into the earth. Both styles had a sunken floor pit, but that of the dug-in house was as deep as six to eight feet rather than the two to three feet of an above ground dwelling.

Like those of other Salish cultures, Tillamook women were highly skilled weavers. Hats, mats, purses, and baskets were woven from fibers of cedar bark and cedar root, spruce root, cattails, ferns, and grasses. Designs were intricate, and dyes, derived from plants such as Oregon grape root and seaweed, added pleasing color. Cooking baskets were woven tight enough to hold water.

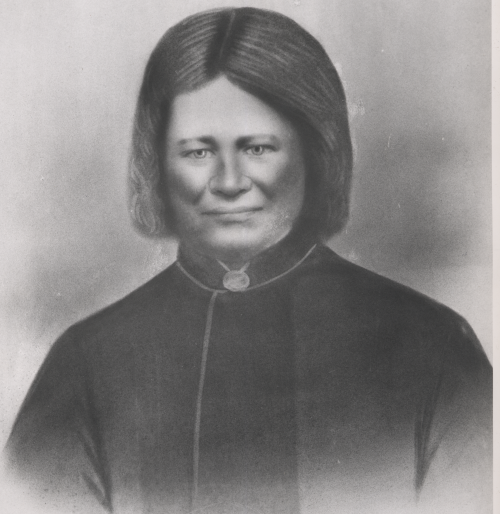

The best-known Tillamook personage was probably Kilchis, a large man with partial African features who had great skill at settling disputes and claimed to be descended from a crew member of the Manila galleon that wrecked on Nehalem Spit in the late 1600s or early 1700s. Though often referred to as Chief Kilchis by the white man, he had less hereditary claim to the title than his contemporary, Illga (or Delga) Adams, who had upper class status. Adams, a skilled canoeman, regularly paddled from Tillamook Bay to Astoria to trade at the Hudson’s Bay Company and once navigated down to California.

The decline of the Tillamook nation began prior to Captain Gray’s arrival at Tillamook Bay. Smallpox, possibly contracted from shipwreck survivors, was already taking its toll. Fur traders arrived, and the trappers who followed Lewis and Clark vastly depleted fur-bearing game. By the early 1850s, white settlers were homesteading on former native lands. The Nestuccas moved south of Cascade Head to live near the Neachesna, but in time, most of this land would be taken from them as well.

The Siletz reservation was created in 1855 and included most of the home territories of the Siletz, Neachesna, and Nestucca bands. In the mid-1870s, the northern portion of these lands was illegally seized and opened to non-native settlement.

The Tillamook proper and Nehalem bands were never required to move onto a reservation. A few of them, led by Illga Adams, camped on property near Hobsonville, south of Garibaldi on Tillamook Bay. In later years, this group consisted of elderly widows whose oral traditions contributed greatly to our knowledge of tribal history, language, and customs.

Today, the Tillamook people are represented by the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians with one or two families married into the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. Descendants of the Nehalem and Clatsop peoples have formed the Clatsop-Nehalem Confederated Tribes, but have not yet been granted federal recognition.

The Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians has a current membership of 5,400, including 30 tribes and bands formerly distributed from northern California to southern Washington. Preservation of the history and culture of each band, as well as historical sites, is a primary tribal goal along with instilling in future generations knowledge and pride in their heritage.

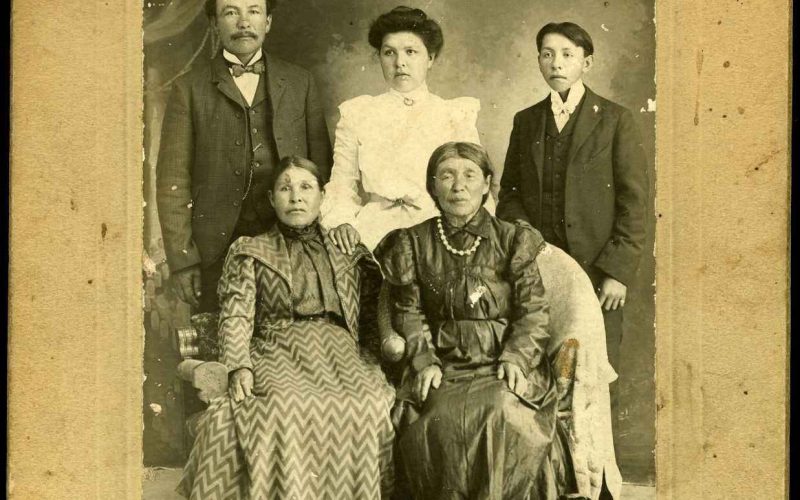

Photo at top of story: Hannah Hawalegas Dick and family. Standing left to right: Henry Curl (Kalapuya), Sophia Dick-Shellhead-Holland-Johnson-Simmons, Fred Dick. Seated: Agnes Dick Curl, Hannah Hawalegas Dick. Photo courtesy CTSI Culture Department

SOURCES

Books:

The Nehalem Tillamook by Elizabeth D. Jacobs, Oregon State University, (Corvallis) 2003.

Tillamook Indians of the Oregon Coast by John Sauter and Bruce Johnson, Binfords & Mort, (Portland) 1974

Oregon Indians by David Agee Horr, Garland Publishing Inc. (New York & London) 1974

Online:

“Indians 101: The Tillamook Indians” Kos Media LLC (U.S.) www.dailykos.com

Tribes of Oregon: Tillamook Indian Nation banksfourthgrade-nativetribes.weebly.com/tillamook.html

“The Spirit of the Tillamook People” by Brian D. Ratty www.dutchclarke.com

“Tillamook (Native Americans of the Northwest Coast” what-when-how.com

“Our History — Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians” www.ctsi.nsn.us

“A Language All But Lost” Tillamook Headlight Herald www.tillamookheadlightherald.com

“Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde” www.grandronde.org

“Clatsop-Confederated Tribes of Oregon—AAA Native Arts” www.aaanativearts.com

“Hobsonville Indian Community” www.oregonencyclopedia.org

This web-exclusive story was posted on January 16, 2020. Please do not post the story, or use any photos included in this story without permission from Oregon Coast magazine or contributing photographers.