STORY AND PHOTOS COURTESY RANDY CORRIGAN

The author reminisces about adventures with his grandpa

as he worked logging operations on the coast and beyond.

Not a word to your mother about this,” Grandpa Charlie said to me as we walked across a log raft on the Willamette River at the rail log dump just south of the River Road bridge in Independence, Oregon. It was 1955. I was 4 years old and didn’t know how to swim. Grandpa Charlie kept a tight hold of my hand as we traversed several logs in the raft, “sizing them up,” as Grandpa would say. He knew if I told my mother about walking on the log rafts, it would be the last time I would get to go on the job with him. As my brothers and I grew older, we would hear Grandpa Charlie make that remark several times!

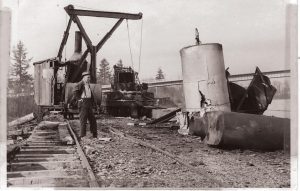

standing by the old steam donkey at the log dump

in Independence; note the River Road bridge in the background.

Charles H. Corrigan was a rail logger in southwest Washington from the time he was 16 years old, when his father died from a logging-related accident and Charlie had to work to help support his mother and five younger siblings. Later, when Grandpa Charlie married and had his only son Ken (my father), he enjoyed taking my father on the job with him. Dad always said going on the job with his father was fun and interesting, watching how the logging crews demonstrated their versatility in every aspect of this business. But one of the best things, according to Dad, was going to the camp cookhouse for great meals, always hot and fresh, something that he got to do two to three times a week as a youngster. On the other hand, my dad always said that his mother wasn’t the greatest of cooks. For instance, dad told us brothers that his mother’s idea of tomato soup was to take a nearly empty bottle of ketchup, fill it with water, shake it up and heat it, and there it was—tomato soup!

Grandpa Charlie carried his enthusiasm to my brothers and me in the 1950s and 60s, first taking me to the Independence operation in 1954 and 1955. When Charlie’s responsibilities expanded in a new job with Georgia-Pacific in 1956, as railways and waterways manager for several rail logging operations in Oregon and California, his “crew” size increased with my brothers Lance and Shawn, as they became old enough to participate. In addition to the Valsetz/Independence operation, Grandpa Charlie’s responsibilities grew to include job sites in Siletz/Camp 12/Toledo, Cottage Grove, Coos Bay/Coquille/Myrtle Point/Powers, Big Lagoon/Samoa, California, and Feather River/Oroville, California.

The cookhouse wasn’t an option anymore with my brothers and me as Grandpa Charlie’s new work with G-P didn’t take him to the remote logging sites. But Grandpa always made sure we ate a good breakfast, either homemade by him or at a favorite restaurant, before heading to the day’s job. My brothers and I rode many steam locomotives, learning some of the engineer and fireman duties. We even got to sound the whistle and ring the bell at appropriate times. We also rode with work crews on speeders as they went out to replace railroad ties and check suspect rails and rail beds.

the North Bend News about the “log puller”

tugboat Randy K when it came through

North Bend enroute to Bandon. It was

launched and moved upriver to Coquille

where it did its work for G-P.

By today’s standards, rail logging then was definitely “old school.” A steam locomotive brought the log trains from Valsetz (now an abandoned “company town” located in the coast mountains east of Lincoln City) to Independence. There, a steam donkey would dump the log load off of each rail car, one car at a time, into the Willamette River. As each car was positioned in front of the donkey, cables were arranged around the log load and then connected to the cable drum on the donkey. Then, the donkey went to work with four to five loud and strong puffs of steam to lift the logs from the rail car, forcing them to roll down the log slide and into the river. The same process was repeated for the Siletz River watershed-Toledo operation. It was similar for the Powers-Coos Bay run, but by then steam had been replaced with diesel-electric power.

The steam donkey was a versatile logging tool with a wood-fired boiler for steam, which powered a piston that turned a drum wound with working cable. In remote logging areas, it could be used to pull fallen timber into a loading site where the logs could be further transported to a desired destination. At the loading site in Valsetz, one was used to transfer logs from off-road log trucks onto rail cars, while the donkey at Independence was configured to unload logs from rail cars into the Willamette River. Grandpa Charlie even bragged to us about the time he used the donkey at Independence to pull a derailed locomotive back onto the tracks. The Coos History Museum in Coos Bay has an old logging steam donkey on outdoor display. They also have a toy steam donkey on occasional display that my dad made for me when I was about 8 years old.

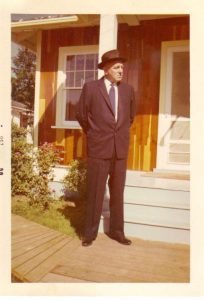

Charlie dressed when we went on the job with

him; the photo was taken as he was

entering his Coos Bay office.

Charlie had my brother Lance and me in mind when he commissioned two 34-foot “log puller” tugboats, the Randy K and the Lance B, in 1957. The Randy K worked the G-P mill operation in Coquille and the Lance B was used at Toledo.

Another “don’t tell your mom” incident happened in 1960 when Grandpa Charlie took Shawn, Lance and me, plus a friend of ours, to inspect rail bridge work on the South Fork of the Coquille River, south of Myrtle Point. We went swimming in the river below the bridge with us older boys in charge of Shawn, as Shawn was just shy of 5 years old and could not swim. Grandpa kept a watchful eye, however, and when Shawn ran out of river bottom, Grandpa Charlie waded in up to his waist before us older boys could react, and brought Shawn back to safety. Not a word was spoken!

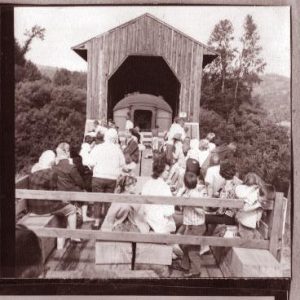

In the spring of both 1961 and 1962, G-P authorized Grandpa Charlie to put together public train rides out of Cottage Grove and Myrtle Point. The Cottage Grove run went up the Row River valley and back for a 32-mile round trip on two weekends. This run was done with a diesel engine and had coach and open cars with a caboose. The Myrtle Point run went to Powers and back with the same type of cars, again on two separate weekends. The big difference with the Myrtle Point ride is that Grandpa Charlie used one of the two reserve steam locomotives out of Powers to make the runs. These engines, the #10 and #11, were a matched pair of “saddle tank” locomotives. With saddle tanks to carry water and fuel incorporated into the locomotive, it eliminated the need for a tender car behind the locomotive. Grandpa Charlie put my brothers and me on the locomotive for all the runs and it represented the last time we got to ride in a working steam locomotive, again performing mostly fireman-type duties along with some minor engineer duties. The run from Myrtle Point to Powers was a beautiful one, with several covered bridges over the south fork of the Coquille River and wonderful scenery each way.

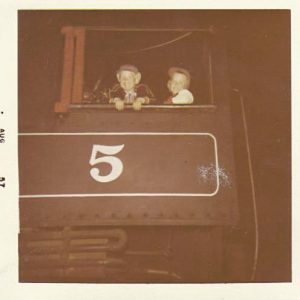

(left) and Randy Corrigan on the #5 steam locomotive at Camp 12 near Siletz in 1957.

The steam locomotives my brothers and I rode on at the Toledo operation have been on static display since their decommissioning in 1960. The “One Spot” locomotive sits at the Yaquina Pacific Railroad Historical Society museum in Toledo and the #5 locomotive is at Avery Park in Corvallis. The “Circle 3,” as it was known in Toledo, but which in fact was the #104 from Coos County, is now back to its original #104 designation at the Oregon Coast Historical Railway museum in Coos Bay.

During one of our last outings, Grandpa Charlie took my brothers and me to a floating wooden walkway on Isthmus Slough next to the G-P plant in Coos Bay, just north of the car bridge over the slough from Coos Bay to Eastside. A dredge with a large crane on it was removing pilings that held the walkway in place and we had to retreat to a safe part of the walkway as each piling was removed. At one point, it appeared the dredge was getting too close and I asked Grandpa Charlie if it would be wise to move further back, but Grandpa said we were safe. However, as the dredge starting to remove the next piling, the walkway came apart below us. Not wanting to go for a swim in Isthmus Slough, Grandpa Charlie hustled us back to a safe section of the walkway. Once we got there and turned around, the place where we were previously standing was gone.

over the South Fork Coquille River.

Grandpa Charlie’s response was predictable, “Not a word to your mother about this!”

This story appeared in the Winter 2019-2020 issue of Oregon Coast Magazine.