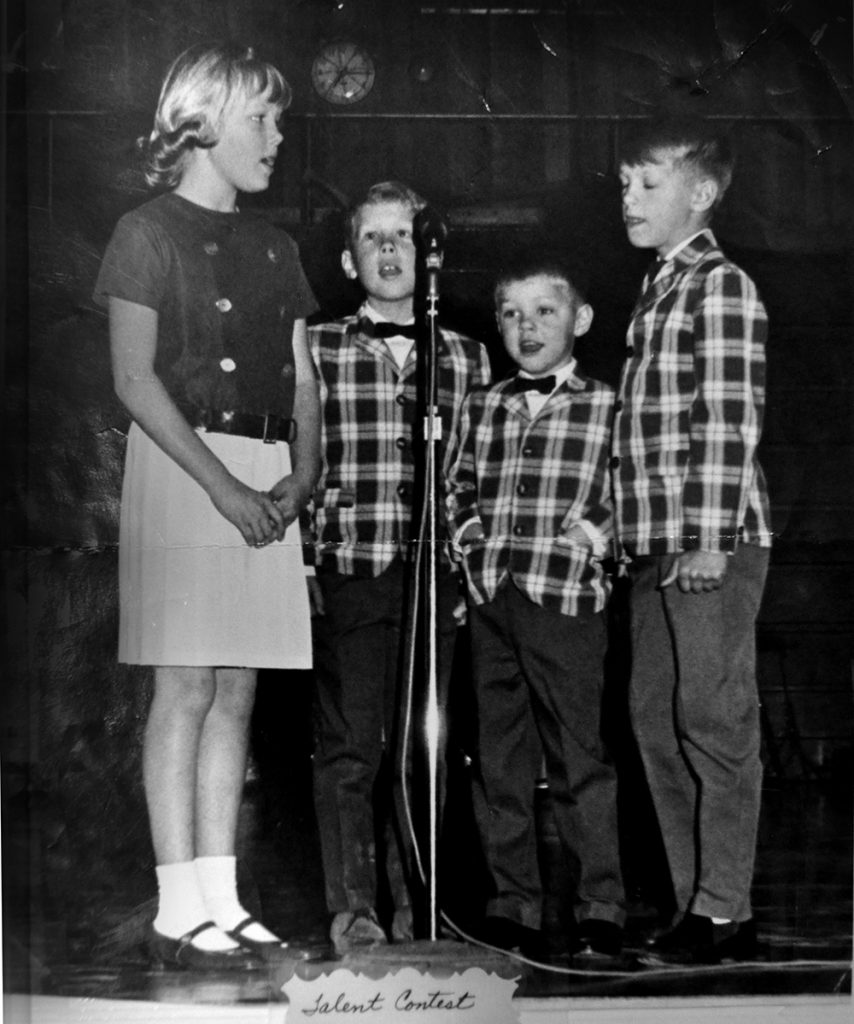

Story and photos courtesy GAIL OBERST

With the help of a recording from the 1960s, Gail Oberst recalls her family’s harrowing adventure in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness.

If I had to rely on my childhood memories, I could tell you very little about being lost at the northern edge of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness, east of Gold Beach and Brookings. But luckily, I don’t have to remember, because the tale was recorded a few years after the drama in an interview conducted by my uncle, Norm Oberst, then-owner of KURY, a Brookings radio station. With the rustling of maps in the background, Norm’s deep, resonant voice questions my late father and mother on the details.

ADVENTURE CALLS

I can picture my dad Bruce on the day of the hike in August 1962: a vigorous, adventurous, 28-year-old father of four. He parked the family’s VW bus at the Rogue River–Siskiyou National Forest trailhead leading to Lawson Creek, excited about this fine summer afternoon jaunt to the creek and back with my mom (Bonnie), me (6 years old), and two of my three brothers, Bruce Jr., 5, and Doug, 3.

The Kalmiopsis Wilderness, just a mile south of where we parked, was much in the news that year because it was soon to be a federal Wilderness Area. Today, the 180,095-acre parcel includes the headwaters of the Chetco and North Fork Smith rivers, and a portion of the Illinois River, into which Lawson Creek flows.

“This is a harsh, rugged area with a unique character,” reads the US Forest Service description. That much has not changed since 1962. In the recording, Dad admits that Mom tried to talk him out of the hike that day. But as they parked at the trailhead, with its prairie-like entrance, the hike seemed easy and approachable. There was another car there, which Dad recognized as belonging to the geology students we had met the night before at Elco Camp. Before we set off, Dad left a note on the student’s car window: “Ha Ha! We found you. We’re hiking to Lawson Creek.”

Little did he know this friendly taunt would possibly save our lives.

In retelling the story, Dad did not dwell on what must have been the easy late-morning hike downhill toward Lawson Creek through small meadows and ancient forests. He was armed with his quad maps and invincible youth.

HIKE TO DANGER

But as the day turned to hot afternoon, attitudes changed. The children tired. “The hike was tougher than I thought,” Dad said. “The kids started crying and had to be carried.” At one point, Dad tripped, little Doug in his arms, and fell head over heels into a muddy, rocky creek. Doug was unscathed, but Dad crawled back up the hill with a bloody elbow.

“Why did you keep going?” In the recording, Uncle Norm is asking the question that had been on my mind for 50 years. Dad answered: According to the map, the trail was a loop. Once we reached Lawson Creek, he believed the trail would return us to the trailhead.

The day wore on. The trail appeared and disappeared. Hemmed in by tall trees and thick brush, Dad could not see where we were. At first, our family followed a small tributary that Dad assumed led to Lawson Creek. Several times, we crossed the tributary on fallen logs, and on one such crossing, little Bruce was swarmed and stung by yellow jackets. Further on, now fearing we were lost, Dad climbed up the side of a steep bank to get his bearings. As he climbed, he dislodged a rock that tumbled down onto little Bruce’s head, raising a huge welt. Down through thick brush we crashed.

Darkness fell as we arrived at Lawson Creek. “By that time, it was beginning to get cold, so we built a fire,” Dad said. He was not yet panicked, but was giving up on returning that day. Dad caught a fish, and Mom fried it on a flat rock over a fire. The hikers had not been completely unprepared, although dressed in summer shorts and light shirts. Mom had packed peanut butter sandwiches, consumed along the way, and Dad had brought along matches and some fishing gear.

I remember the river taste of that fish, and the cold water on my shaking stomach. I was old enough to understand that this adventure might not end well.

“Bonnie was scared to death of rattlesnakes and bears, so we assembled all sorts of weapons—sticks and clubs,” Dad said. Covering the children with branches and leaves, my parents kept the fire going all night, unable to sleep. Dad recalled his children sleeping with their eyes open, a sign of fatigue, he thought.

The next morning, Dad said he thought we could quickly find the trail and hike out. But the longer we followed Lawson downstream, the more convinced he became that we were lost. The creek cut through a deep canyon, and the trail, when we were able to find it, crossed and re-crossed the creek. The children, too weak to hike far, had to be carried most of the time. At one crossing, Dad, two children in arms, slipped on rocks in swift chest-high water. He said we were all nearly washed away.

LEFT HIGH AND DRY

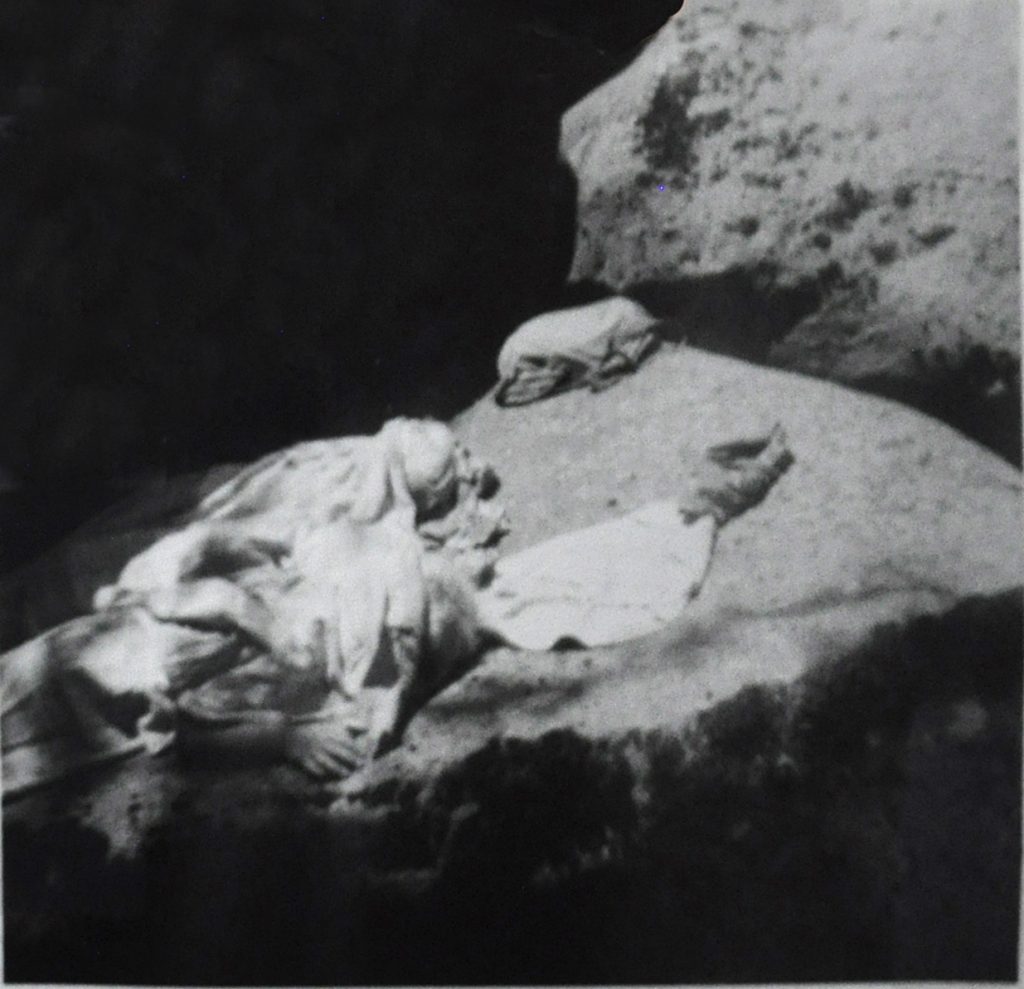

As the morning grew late without progress, Dad made a decision. He would make a camp for his family on a huge rock in the middle of Lawson Creek, at the confluence of another large creek. Unencumbered, he would retrace his steps to the car and get help. On the recording, Mom pipes in, reiterating her fear of snakes and wild animals. The midstream rock, about 25 feet long, 10 feet across, and surrounded by water, was chosen with this in mind.

Dad recalls looking back at his family. “I left my family on the rock,” he said. “I’m the one who insisted we hike down here.” Guilt must have motivated him to find a way out, despite his lack of sleep and sore muscles.

Mom lit a fire with the only match we had left. As the afternoon sun crawled overhead, it grew hotter and the children, lethargic. For the rest of the day, we played in the water, she said, and we dozed. She tried to fish, but caught nothing. Her stomach hurt, she recalled, but she wasn’t hungry. When it got dark, the family gathered around the fire.

“We sang and I told them stories, to keep them from being upset.” All night, she kept the fire going, the colliding creeks around her making a “thunderous roar.” In the dark, she said she envisioned bugs and snakes and bears attacking her children. Instead, the worst attacks came from salamanders that crawled on us, seeking warmth.

The children were uncomplaining and in a stupor, she said. Quietly, she brushed off the salamanders. His family behind him, my father that second day attempted to retrace his family’s steps, back over the ridge away from Lawson Creek.

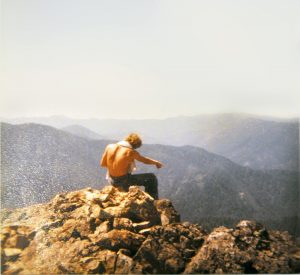

Tired, thirsty, and at times delirious, he found no rest in the rugged terrain. Steep hills had him crawling on all fours. By late afternoon, he came to a familiar clearing with an abandoned barn and a flattened house—an old homestead.

Feeling hopeful, he circled the clearing, looking for an exit to the trail. After an hour, he laid down in the middle of the clearing, “crying like a baby.” It was there, he said, that the heat and exhaustion really hit.

He prayed, and rose to try again. Finally, he found the outlet that led to the trail and out to the car. It was late afternoon. At the parking lot, Dad was met by rangers and the two geology students, already assembling a search. When the young family had not returned to Elco Camp, the students had reported their concerns, along with the note Dad left on their car, to authorities.

It was getting late, and Dad’s instructions were unclear, but the students and the ranger were determined to rescue the family that night. Leaving Dad behind resting on the floor of his VW bus, the search party set out armed with candy bars, trail maps, and powerful flashlights.

RESCUED!

Mom said she woke late at night to the sound of men yelling above the roar of the water, and to lights in the distance, flashing down the hill. She yelled back, and then, they were there. Two young men with candy bars stayed the night on the rock, guarding us until dawn.

Mom, ever modest, remembers during the interview the embarrassment of her torn clothes, and wondered what they must have thought. This I remember about the hike out the next morning— the smell of the strange man, the sickening rocking movement as I was carried along a high ridge trail that overlooked blue skies and endless trees and rock. I remember the watery taste of bile as we stopped along the way while I threw up, several times. My brother Doug refused to be consoled unless Mom carried him. Dad, who greeted us as we neared the car, said Doug’s crying was the first thing he heard. I think he meant: the sound was a relief.

Safely returned to our campsite, Mom and Dad rested for a while, exhausted from the ordeal. But her children, Mom said, seemed unfazed. “They tore around the camp like they had just come out of bed. I couldn’t believe it.”

The tape and the questions wind down. I eject the CD copy and hold it close to my heart. Life can take many turns, I think. Luckily for my family, this turn was not a dead end. ■

This story appeared in the August 2017 issue of Oregon Coast magazine.