Story By Claire Hall

Photo Above: Trail at Cape Perpetua, Oregon. By Dennis Frates

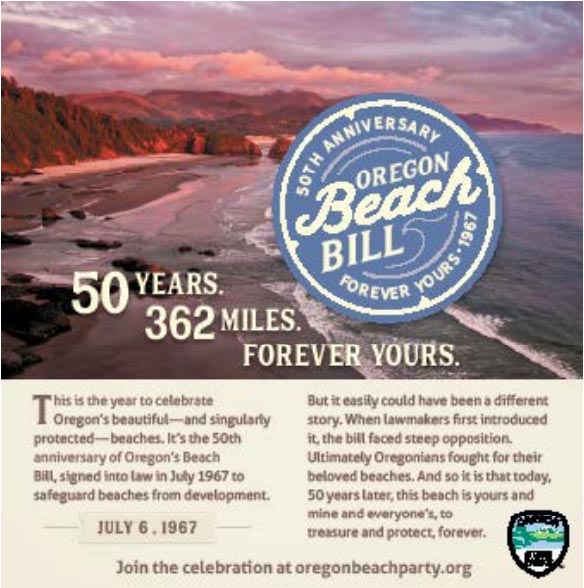

Nothing defines the progressive spirit of Oregon better than the Beach Bill, a state law that grants public access to all of our incomparably beautiful shoreline.  The year 2017 marked the 50th birthday of that landmark legislation. The story of how it came to be looks simple—on the surface. During the 1960s some oceanfront property owners began to erect barriers to limit the public’s access to the beach. Oregon’s governor, Tom McCall, in what could be seen as a publicity stunt, landed on the beach in a helicopter to stare down some motel owners who had put up driftwood log barriers that cordoned off the beach in front of their lodging. McCall’s stunt was, however, the signature moment in a successful campaign that led to the passage of the Beach Bill.

The year 2017 marked the 50th birthday of that landmark legislation. The story of how it came to be looks simple—on the surface. During the 1960s some oceanfront property owners began to erect barriers to limit the public’s access to the beach. Oregon’s governor, Tom McCall, in what could be seen as a publicity stunt, landed on the beach in a helicopter to stare down some motel owners who had put up driftwood log barriers that cordoned off the beach in front of their lodging. McCall’s stunt was, however, the signature moment in a successful campaign that led to the passage of the Beach Bill.

There are elements of truth to that story. But, not surprisingly, the real story behind the Beach Bill is far more complex and instructive.

The first “Beach Bill” in Oregon was enacted in 1913. Its champion was the plainspoken and honest governor Oswald West—a man with strong conservationist tendencies in the mold of Theodore Roosevelt. A model of simplicity and clarity, the bill was just 66 words long and declared that Oregon’s shoreline was a public highway.

Tom McCall was born just one month after Governor West signed the first Beach Bill into law. After serving in the Navy during World War II, McCall pursued a career in journalism (print, radio, and television). During the years McCall grew to maturity, more and more Oregonians began to travel to the Oregon Coast. The build-out of Highway 101 and other highways made that possible. In addition, farsighted decisions to create a network of state parks at or near the beach cemented the idea in the minds of most Oregonians that beach access was a birthright.

But, as it turned out, this birthright was not secure.

By the mid-1960s, state officials were seriously concerned about their legal position in protecting the shoreline. Some private landowners had constructed fills onto the dry sand, but the one that garnered the most attention was when Bill Hay, owner of the Surfsand Motel at Cannon Beach, placed beach logs to create a guests-only area in front of his motel.

A Parks Department study found that 112 miles of the state’s sandy beach were in private ownership to the high tide line. Most people thought then (and now) that the public “owns” the beaches, but in many cases, at least a portion of the sandy area remains in private ownership, but the public enjoys a permanent easement for recreation use.

The Surfsand issue came to the state’s attention in the summer of 1966, and by then, Secretary of State Tom McCall and State Treasurer Bob Straub were engaged in their first battle for the state governorship. These two men would command the stage on environmental issues in Oregon for the next decade.

The state’s Highway Commission presented House Bill 1601 in the 1967 Legislature, the first bill under McCall’s governorship. The measure was designed to clarify the public’s right to unimpeded access to the dry sand beaches. Despite vigorous debate in committee about many aspects of the bill, it flew under the radar and was headed toward the Legislative equivalent of the graveyard (death in committee) when a series of key developments took place.

Matt Kramer, an Associated Press reporter, produced a series of articles that galvanized public interest and led to the House Highway Committee being flooded with more than 10,000 letters and telegrams of support. It was Kramer who named HB 1601 “The Beach Bill.” (Kramer’s reporting is memorialized today with a plaque at Oswald West State Park, the only instance of a public memorial to a working journalist in the state.)

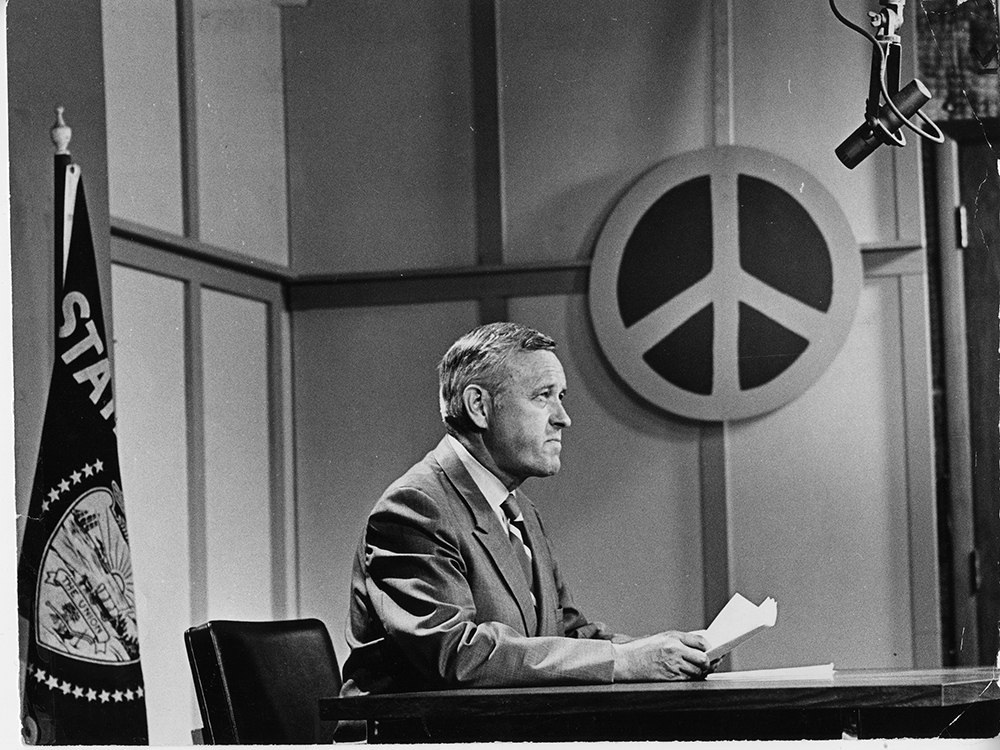

Then McCall seized his bully pulpit. The 6-foot-5 inch McCall, known for his silver hair, prominent jaw, and raspy voice that had come into thousands of Oregon homes for decades, dropped onto the beach by helicopter in May.

The picture of him staring down the Surfsand Motel’s log barrier is one of the most iconic photos in Oregon history. He was also accompanied by experts who proposed a single beach line at 16 feet above sea level. There was much tinkering and back-and-forth, but the final version of the bill easily passed both the state House and Senate and was signed into law by McCall in July.

McCall was proud of his skill as a wordsmith, but in signing the measure, he reached back to the words of his processor, Oswald West, who said: “No selfish interest should be permitted, through politics or otherwise, to destroy or even impair this great birthright of the people.”

This is the story as known to the public. But as mentioned in the beginning, there’s more nuance behind it. For one thing, the 1967 Beach Bill was not the end of the story; the 1969 Legislature passed HB 1045, which established the permanent line of the beach zone following a survey of the entire coastline by the Highway Commission.

The issue of public versus private rights to the beach spawned a series of court battles, which continued for years in both state and federal courts.

The historical record continues to be revised and amplified. Late last year, former Cloverdale State Representative Paul Hanneman, first sponsor of the Bottle Bill, published a memoir that sheds light on the critical role the Legislature played in working through the details and bringing the 1967 and 1969 bills to fruition.

John F. Kennedy once said victory has a thousand fathers and defeat is an orphan. As the landmark 1967 bill has now passed more than 50 years hence, Oregonians will be thanking the many fathers (and mothers)—governor and legislators, reporters and activists, and private citizens by the thousands who stood up and said the great birthright must be protected forever. ■

This story appeared in the May/June 2017 issue of Oregon Coast magazine.