STORY BY GRACE ELTING CASTLE

New interest in both the preservation of existing beadwork and the creation of new pieces ensures that the artful tradition will be passed on to future generations.

For many decades, the beautiful beadwork of Oregon’s coastal tribal members was known only to museum visitors or those with a treasured family collection. Some artists were able to continue their work, but it wasn’t readily available for sale.

Today, there is a resurgence of interest not only in preserving these amazing works of art, but also in developing the skills and talents necessary to bead regalia, jewelry, moccasins, and crowns for the young ladies who represent the tribes as their queen and princesses. Old patterns and beads are still used, but there has been an explosion of new bead stores and unusual projects.

Anthropologist and art historian Lois Sherr Dubin noted in Cowboys and Indians magazine: “…Artistic activity was crucial in helping the Native people survive near cultural and physical annihilation. The women frequently encoded messages understood by their Native community. One cannot help but look at these pieces, stand near them, and feel their power to connect across time and place.”

Most of the tribes of the Oregon Coast, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, and Coquille Indians strive to recapture the cultural knowledge nearly destroyed in the campaign to exterminate native people. In early reservation days, survival was difficult and left little room for pursuing or learning the art of beading.

As the Coast (Siletz) Reservation lands dwindled from over a million acres to final termination in the 1950s, some families retained the knowledge of this art form, but few had enough financial resources to create new pieces.

Those who were fortunate to have beadwork preserved from family members held them dear to their hearts and mostly kept them secret from all but close family members. There are now only a lucky few who can dance their parent or grandparent’s beadwork on their regalia.

When the Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University published The Art of Ceremony, Regalia of Native Oregon to celebrate the cultural artistry of the nine federally recognized Oregon tribes, the booklet featured one item per tribe. The beadwork of some of those tribes is well-known and coveted by collectors and dancers preparing their pow-wow regalia. Though their beadwork is popular and appreciated, the Siletz chose their even more celebrated woven basket cap.

Vice-chair Alfred “Bud” Lane, III noted, “The trauma our people and culture have been through is unimaginable. The survival of our traditions is proof of the resiliency of our community…”

The Coquille Tribe, in the south coast area, chose to display a necklace fashioned after an old necklace in a Ned/Meade family story. The modern necklace published in the booklet is made of dentalia, beads, and five gold Sacajawea coins and is danced to honor their personal family history.

Some coastal museums hold pieces from past artists, the best example being the Burrows House Museum in Newport, which acquired the extensive collection of the late Clarinda Copeland who ran the government store on the Siletz Reservation in early years. Some elders remember hearing it was common in those years for baskets and beadwork to be traded for supplies at her store.

Those artists lucky or determined enough to have learned from an elder are now able to teach the younger people thirsting for a taste of the Native culture, thus passing down a gift. They are beading a variety of items such as moccasins, breastplates, wallets, royalty crowns, necklaces, and earrings. A Siletz beader makes lanyards that are popular with the hundreds of people working for the tribe, which is Lincoln County’s largest employer. Perhaps the most popular of the new projects are the Pop Sockets for the back of a cell phone.

Speaking of the popularity of this art, Jessica Metcalfe wrote in Cowboys and Indians magazine, “…it’s about kinship, value systems, storytelling and perhaps, above all else, it is about love for the mentors, for the ancestors, for the youth, and for the self.”

Unless one is a serious collector or beader, there is little reason to know beading terminology such as Two-needle applique, loom, off loom, or stitch names like Peyote, Potawatomi, Brick, Dutch Spiral, Cellini Spiral, Albion, Herringbone, Ladder and Square. Some of those names are variations of the popular Peyote stitch. Some are associated with the art of specific tribes across the U.S. Diane Fitzgerald, writing in Bead and Button, noted there is “…an astounding round of new and exciting stitches and techniques and they just keep coming.”

For those exploring the coast in search of authentic Native beadwork, it is still difficult to find, though many young beaders are now utilizing Facebook and Instagram to promote their projects. One of the most popular places to see and purchase Native-made items, including beadwork, is at the pow-wows held at each of the tribal headquarter villages or at their casinos, some of which also offer beadwork and other craftwork in their gift shops.

Ezra’s Gift

—By Grace Elting Castle

My life has been filled with mysteries. One of the longest-lasting has been the man named Ezra Simmons who made my beaded moccasins before I was born.

People seldom talked to me when I was a child. I learned from what I heard them say about me. I didn’t learn much about the Ezra Simmons who had made my moccasins except that people always spoke his name in hushed tones.

In time, I realized he was my uncle’s deceased brother. I won’t explain all the trauma from learning that a deceased person had made my gift, but my child mind was greatly relieved when someone finally mentioned that Ezra died after my moccasins with their beautiful beaded flowers were finished.

I heard more about Ezra as the decades rolled past and I learned to ask questions.

He was, indeed, my Uncle Ed’s brother, both members of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians. He had passed away at the age of 44, due, his relatives believed, to complications of polio. My moccasins were one of many beautiful items Ezra beaded. I also heard that he had been a talented musician and his band played at community dances in the Logsden area of the reservation.

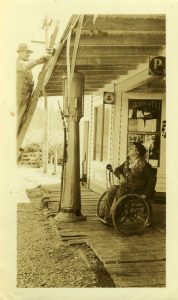

There is an interesting story remembered and passed down that Ezra used to sit in his wheelchair in front of the old Bensell’s Grocery store on Siletz’s main street to do his beadwork.

Eventually I lived in the house that Ezra had lived in with his parents Hoxie and Lizzie Simmons, whom I had considered my grandparents because they were to my cousins. My little moccasins were always on the bookshelf in that house and in all my later homes.

Recently, while collecting photos and words for the article on beadwork, I was introduced to toys known as “Ezra’s dolls.” He made them with alder wood heads, drew their faces, and beaded the deerskin clothing. His business stamp still clearly shows on the back of the dolls’ cradleboards. The dolls are waiting for the new culture center and museum to be built, a special project of the non-profit group, Siletz Tribal Arts and Heritage Society (STAHS).

We may never know the extent of Ezra’s creations, but there are others, tribal members, who have his little moccasin gifts and I’ve seen beautiful beadwork in the homes of his relatives that could easily be his artistry.

Ezra Simmons in 1943. Photo by Grace Castle

It has been exciting to see these two photos of Ezra, but they elicit more mystery, more questions. Could he still play the fiddle for dances after he was in a wheelchair? Are there examples of his work in other Oregon museums? Why haven’t I found his obituary? When can I visit the Burrows House in Newport again to look for Ezra’s art? The search continues.

This story appeared in the Winter 2019-2020 issue of Oregon Coast magazine.