Whether met tumbling in the surf, bubbling from beneath the sand, or stranded by the receding tide, the lowly Pacific mole crab, or sand crab, deserves a second look. While not the most glamorous of our coastal wildlife sightings (some say creepy), this simple, ancient crustacean—the size of a big toe—offers fascinating study. It excels in two areas, multiplying (staying ahead of the appetites that would devour it) and digging (hence the name, mole crab).

Nomadic, with an existence tied to tides and storm, the mole crab lives along sandy beaches between Alaska and Chile in the dynamic and ever-shifting swash zone, where tides break and run up shore. Sand, key to its survival, provides the mole crab an anchor for feeding and a hiding place from predators. By feeding on microscopic organisms and serving as a critical foodbank for fish (primarily surf perch), gulls, shorebirds, and surf scoters, the mole crab has become an indicator species for evaluating the health of our prized shores.

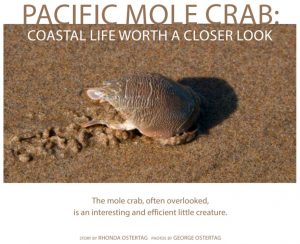

A person would be hard-pressed to find a more nondescript creature or a more perfectly designed one. This simple, harmless crab sports a drab, pale gray or brown fragile shell that measures 1.5 inches long and 1 inch wide. It is ovate or egglike in shape, equally boring. But why draw attention when you’re the food? The mole crab’s pointy rump allows the backwards digger to easily pierce the sand.

Then, with its tail it whips the saturated sand into a slurry, allowing for quick escape beneath the surface. With the adaptation of paddle-like front feet in place of claws, the mole crab can efficiently push away the displaced sand. Its five pairs of legs further help in the artful escape or with crawling or swimming. From start to finish, a dig takes but 1 to 7 seconds. Should you encounter a mole crab stranded on its back, a simple assist to upright is usually sufficient to initiate a dig. In a blink what rests before you are the bubbles of a perfect excavation machine. The mole crab has two pairs of antennae, which protrude from the hole of its shallow burrow. One pair serves breathing. The other, feathery topped, sieves plankton from each watery pulse over the hole. The telltale bubbling after the tide retreats is often the lone clue to the life beneath one’s feet. The preferred state for the mole crab is submersion. Time atop the sand is time in danger.

Females, larger than the males, can produce tens of thousands of eggs per month, which require 30 days to mature. Molting precedes reproduction. After hatching, mole crabs start life in the water in a planktonic state and undergo up to 11 larval phases. On return to the beach as adults, their lives span 18 months, with the males dying off after the second summer, and the females by that winter.

On the beach, you will find the mole crabs arriving in numbers. Some experts attribute the behavior to convenience for mating or perhaps safety. Others point to environmental conditions.

You may encounter mole crabs spring through fall, with the crustaceans most active spring and summer during molting and mating. During such times, the saturated sands can undulate. Gulls walk around sated. In winter, the storms that carry away the beach sand also carry away the mole crabs. But spring brings another chance to build an acquaintance. Walk up and say hello. ■

This story appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of Oregon Coast magazine.