Story by CHERYL D. WANNER

Shark encounters are rare on the Oregon Coast, but they do happen.

April 22, 1998, was a perfect day for John Forse of Lincoln City to try out his new surfboard. Arriving at Gleneden Beach and finding blue skies, offshore winds, and a good swell, he spotted other surfers already in the water. But one of them—Randy Weldon, also of Lincoln City—called it quits shortly after Forse paddled out, saying he had a weird feeling. The others followed Weldon in, leaving Forse with the water all to himself.

From the corner of his eye, Forse saw a flash of movement. He attributed it to sea lions, but then something grabbed both his thigh and board in a sandwich grip and dragged him underwater. John saw the dorsal fin so close he could almost touch it and instinctively pounded on the back of what would later be estimated as an 18-foot white shark. He was released, but the shark still had the surfboard leash in its mouth, and when it dove down, Forse was dragged down with it. Unable to free his ankle from the strap, he figured this was the end. But the shark cut the leash with its teeth, and Forse shot to the surface and swam for his board, floating upside down on the surf. Once ashore, his friends gave him a lift to the hospital, where he was treated for a not-too-severe bite wound.

Shark encounters are actually quite rare off the Oregon Coast. Only 28 incidents (all unprovoked and non-fatal) are listed in the Global Shark Attack File for Oregon, and most of these are surfboard bites, though a few involved bodily injury.

The white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is responsible for all identified species incidents on the Oregon Coast. With its jaw thrust forward and the roof of its mouth and palate pulled back into a jagged-toothed maw, it can look like your worst nightmare. But far from the myth of Jaws, white sharks, aka “great whites,” are not mindless killing machines. They are social animals with a high level of intelligence and complex behavior. Inquisitive by nature, they just might decide to check out a pair of legs dangling from a surfboard or paddling through the water.

Most human/white shark encounters resulting in injury are actually exploratory bites. “White sharks use their mouths like a hand; their teeth can feel and explore objects the way we use our fingertips,” says Mark Marks, research biologist, shark specialist, and founder of the Shark Protection and Preservation Association.

Bites typically occur because the shark is trying to get a handle on what it’s seeing.

When going for the kill, the white shark often shakes its head laterally, sawing back and forth with its teeth to dismember sea lions or seals or tear chunks of blubber from a whale. When merely exploring or taste testing, it will bite down and then let go, rarely coming back for a second hit. This sampling technique is consistent with most white shark/human interactions involving wounds or object bites, such as surfboards. Though there are recorded incidents of humans being consumed by sharks, such behavior is rare. Most fatalities result from tissue damage and blood loss due to the initial bite.

Of the many species of sharks found in Oregon’s coastal waters, only the white shark poses a threat to man. White sharks spend time offshore, but tend to patrol inshore when searching for prey. This sometimes brings them in contact with surfers.

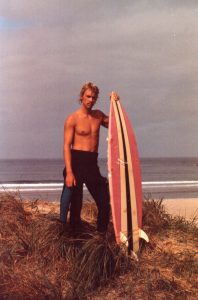

Randy Weldon, who’d felt something was amiss the day John Forse was bitten, came by his premonition naturally enough. Weldon, surfing a sandbar just south of Cape Kiwanda in 1983, had paddled out to catch the next wave set when something came up from below and bit his surfboard. The impact threw him several feet into the air. “I remember seeing the shark, but my mind wouldn’t accept it,” said Weldon, then 23. “I tried to figure out what was happening. Did someone paddle or surf into me? Did a sea lion hit me?” Surfacing and seeing a shark chomping on his board brought reality home. Weldon tried to paddle away, but his ankle was leashed to the board. The shark finally let go and headed west toward Haystack Rock. Stroking hard for shore, Weldon saw it coming back around from the south only to submerge just yards away and disappear. Shark experts believed it was a white with a length of 16 feet and a weight of 3,000 pounds.

Most recently, Joseph Tanner, a critical care nurse at Emanuel Hospital in Portland, was severely bitten in the thigh and lower leg by a white shark off Indian Beach in Ecola State Park. In October 2016, Tanner was hanging vertically in the water, arms on his surfboard, when the shark grabbed his right leg from below and pulled him under. “My whole leg was in its mouth,” he said. “I thought I was going to die.” Tanner repeatedly punched the shark in the gills, and it let him go. He was able to grab his board and paddle ashore, rolling off into six inches of water where several people dragged him in. Tanner directed his own emergency procedures. He knew his blood type and told a bystander how to tie a tourniquet with his surfboard leash.

He was airlifted to Emanuel (per his request) where he was hospitalized for nine days and underwent multiple surgeries. He bears the shark no ill will and has every intention of getting back into the water as soon as he is able.

Both John Forse and Randy Weldon are still actively surfing. Following his encounter in 1998, Forse explored the Nelscott Reef in Lincoln City and now hosts the Nelscott Big Surf Classic, which attracts surfers from around the world. These guys know the risks, but they also know the chance of a repeat encounter is extremely low. You’re much more likely to get hit by a car, struck by lightning, or meet up with any number of work-related or natural disasters than to be bitten by a shark.

And thanks to the work of shark biologists, a new picture is emerging of this apex predator we’ve feared for so long. Precautions are, of course, in order. But as knowledge replaces myth, perhaps we will have less fear and more respect for this creature in whose world we are merely a guest. ■

ABOUT WHITE SHARKS:

WHITE SHARKS ARE the largest predatory fish in the ocean, reaching lengths of up to 20 feet and often weighing more than 4,000 pounds. They are torpedo-shaped, gray on the back and sides and white underneath, and more heavily built than most shark species. They have roughly 50 teeth in their jaws that are easily lost in consuming prey and promptly replaced by developing backups. White sharks are essentially warmblooded fish. Through a process known as point-endothermy, they can generate their own heat to specific organs rather than relying on the temperature of surrounding waters, thus increasing their speed and maneuverability. And through their ability to sense electromagnetic fields, they can detect the heartbeat of fish lying motionless as well as the motor of a boat on the surface. White sharks spy hop and breach, as whales do, sometimes launching completely out of the water in pursuit of prey. They feed on a wide variety of marine life, including fish, pinnipeds (seals and sea lions), dolphins, and whales. Females tend to be larger than males and give birth to live pups. While the life expectancy of the white shark is unknown, it is speculated to be 45 to 75 Years.

REDUCING THE RISK OF SHARK ENCOUNTER

SHARKS FEED PRIMARILY at dawn and dusk, so it is best to avoid the water at those times of day.

DON’T GO IN if you see seabirds feeding offshore—something much bigger may be driving bait fish to the surface. Avoid estuaries as they involve more fish, more food chains, and therefore more predators. For the same reason, don’t go near seal and sea lion colonies or where people are fishing.

DON’T URINATE in the water. While the urine itself dissipates, the residue clinging to your swimsuit or wetsuit broadcasts a flight-or-fight scent that is an attractant to predators, much more than blood.

KNOW WHEN SHARK populations are highest in your area. In Oregon, that would be late summer into mid-fall. Salmon migrations run from August or September through October, and sea lions are also more abundant at this time of year.

ENCOUNTERS OFTEN OCCUR inshore of a sandbar, between sandbars, or near dropoffs where sharks may lurk in search of prey. Not only do they have a keen sense of smell and sight, but they also detect pressure waves and electromagnetic fields.

IF YOU SEE A SHARK, promptly go ashore, preferably in a non-panicked state. If you are bitten, punch the shark in a vital area such as the gills, eyes, or nose. Wearing the thickest wetsuit available can help minimize injury. And knowing your blood type and how to tie a tourniquet could save your life.

This story appeared in the July/August 2017 issue of Oregon Coast magazine.