The good, the bad, and the ugly about purple sea urchins.

STORY & PHOTOS BY JOANNE CARROLL-HUEMOELLER

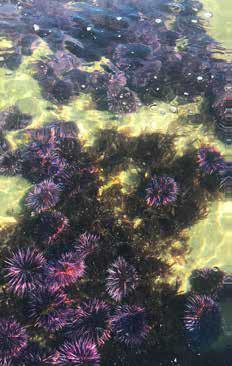

Would the term consequential describe a day in the life of a simple purple sea urchin? Probably not. This prickly invertebrate is nothing more than a round test (hard shell) covered with spines, threadlike tube feet and a mouth hidden below. Intestines, a water vascular system and a nerve network support bodily functions but there is not a heart or a brain to be found. There are gonads, but we will save them for later.

In the best of all worlds, ocean currents and wave action regularly deliver a feast of drift kelp to the waiting urchin. In that world, the urchin does not need to search for food. Along with no need to forage comes no need to move. Transporting the free meal from the aboral surface to the waiting mouth below is about as active as this creature gets.

The two top urchin predators along the central California coastline are the sunflower sea star and sea otter. Hunted nearly to extinction in the 1800s, these sea otters have made a substantial comeback. Sea otters remain mostly absent from the northern California and Oregon coastlines. When sea otters are missing, it is up to the sunflower star to keep the purple urchin population in check.

Most often, all goes well. But there is always a hiccup. What started as something small and relatively insignificant quickly grew into an unprecedented catastrophe leaving nature totally out of balance. This is a story of echinoderms, in particular the purple sea urchin and the sunflower sea star, and rising ocean temperatures.

SUNFLOWER STAR DISAPPEARS

By 2014, an unparalleled die-off of sea stars was underway. The cause was sea star wasting syndrome, a disease that seems to flourish in warmer waters. Sea stars just melted away. Among those most significantly affected was the sunflower star, which literally disappeared from west coast ecosystems. The purple sea urchins of northern California and Oregon were left with few, if any, predators.

About the same time, these spiny pincushion-like invertebrates had stunningly successful breeding seasons, again, possibly a result of warming oceans. The perfect storm was beginning to brew. With no predators and record spawning seasons, purple sea urchin numbers exploded. We are talking by hundreds of millions, 350 million on just one Oregon reef. That’s a mind-boggling jump of 10,000 percent!

The current could no longer keep up with the drift kelp demand and urchins were becoming increasingly ravenous. So, what do they do? They start to move. Masses of them. They do so by using both their spines—which are attached to the test by ball and joint sockets—and tube feet that are supported by the water vascular system.

Now they are actively foraging, bulldozing through and devouring magnificent living kelp forests. All the while, they continue to reproduce in record numbers. The result is urchin barrens—think of a clear-cut forest. Nothing is left. Kelp forests that once provided diverse habitats and food for a whole host of invertebrates, fish, marine mammals, and algae have vanished. So have all the plants and animals that depended on them.

The devastation began in northern California and spread into Oregon. Here is the dilemma. While many kelp forest-dependent species die off due to starvation or lack of habitat, the purple sea urchin does not. They merely go dormant. Think about this. Their life span is 30 or more years. Kelp forests had already been struggling. They are less resilient and their growth less robust in warmer water. That will be a factor in kelp forest regeneration. If and when that might happen, hungry urchins will always be there waiting.

The question is, where are we today and where will we be next month, next year, or even further down that road? According to Scott Groth of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the purple sea urchin population is “…probably holding steady with some natural mortality.” He qualified that, though, as being anecdotal. If that is indeed the case, it is a small step in the right direction. Unfortunately, he could not share better news regarding the awesome, 24-armed sunflower star’s return to our rocky shores and to its role as a top purple sea urchin predator.

URCHIN FARMING

When a situation leaves us feeling helpless, we humans often get creative. This crisis is no exception and is where the aforementioned urchin gonads become noteworthy. First a little background. There is a market for the much larger red sea urchin’s roe, known as uni and held in high regard by the palates of sushi lovers. Until now, purple urchin gonads had been overlooked due to their much smaller size.

With a vision for the future and a good dose of imagination the theory of ranching purple sea urchins for their gonads evolved. Human divers would become this urchin’s new top predator. Purple urchins would be collected from the ocean’s rocky reefs, put in fresh seawater tanks, fed well with farmed algae to increase the size of their gonads and taken to market.

Beyond reducing the number of urchins on the ocean floor, the appetite for uni could make this endeavor rewarding economically as well. There are profits to be made and jobs to be created.

Work to this effort is being done in Port Orford in an “urchin ranching” pilot project run by the Oregon Kelp Alliance in partnership with the seafood company, Oregon Sea Farms. According to Tom Calvanese, Kelp Alliance coordinator, purple urchins are plucked from the ocean and raised in land-based tanks, where they are fed dulse (a dark, red edible seaweed that is also readily grown in onshore tanks) until they reach market quality. In addition to raising marketable urchins, the goal of the project also includes the restoration of kelp beds. Will it be successful? Only time will tell.

As it turns out, the purple sea urchin is a main player in an oceanic world turned upside down. That makes a day in its life considerably more consequential than might first have been thought.

FYI

The Oregon Kelp Alliance (ORKA) coordinates with multiple interests to develop strategies to understand and promote healthy kelp forests, including the pilot purple urchin removal project. Members include commercial urchin divers, researchers, managers, conservationists, tour guides, sport divers, chefs, and other community members.

Oregon Sea Farms, located in Port Orford, specialize in collecting and cultivating sea crops in the Pacific Northwest, including seaweeds such as dulse.

For more information, including video and photos on the purple urchin problem, visit the Oregon Marine Reserves web story “A Prickly Problem with Sea Urchins.”

This story appeared in the Fall-Winter 2020 issue of Oregon Coast magazine.