One woman describes her time as a fire lookout on the south coast in the late 1950s.

STORY BY THERESA VERBOORT

Driving south of Coos Bay, on Highway 101, my mind always flashes back to my stint as a forest fire lookout, when I was a new graduate of Bandon High School, the class of 1958 and just 17 years old.

Jobs for young women were almost non-existent in the area, and I desperately needed to make money for college. But I had an uncle who was related to someone in the Coos Forest Protective Association, who put in a good word for me. With his recommendation, they checked me out and hired me as a lookout for the summer.

The whole experience was thrilling to me. It was my first adventure away from home. I would have my own place to live for the first time in my life. And I would be responsible for thousands of acres of land, protecting them from the horrendous fires that could devastate entire forests in the hot, dry months of summer. It was an important assignment.

Those of us who were to occupy the lookouts were given a day of training to teach us the fire regulations and how to use the fire finders.

The fire finder consisted of a round, topographic map, sitting on a pedestal in the center of our glassed-in lookout cabin. The map was divided into 40-acre sections of the land we would be able to oversee from our lookouts. The sections were divided into quarter sections, which were again divided by four. We were taught how to turn the sight piece, which sat on a sliding metal ring that encircled the map and had a long, straight wire attached to the cross-hairs on the opposite side, to line it up on a “smoke.” With this we could figure out where it was located by using landmarks, such as odd shaped mountains, or perhaps roadways or buildings, or by counting the ridges between us and the smoke. It was really a pretty accurate means of location. We then were taught how to use the shortwave radios to call in the location of the smoke.

My parents were not so enthusiastic, especially my mother. She was concerned about my being isolated and alone for so long. My less emotional father made sure I took his .22 rifle and made me practice firing it. They also loaned me the family dog, a black and white little short-haired mongrel named, imaginatively, Spot. They bought me a month’s supply of groceries, mostly non-perishables, and gave me much advice about being careful. I packed my jeans and essential outdoor clothes and was ready and eager to go. I wasn’t worried about being alone, having spent many hours by myself in the woods surrounding our house. Like most teenagers, I was invincible.

My first summer, my parents drove me and Spot and all my gear to the Four Mile Ranger Station south of Bandon. There I met my supervisor, we’ll call him Bill Jackson, since I can’t remember his name. Bill was a jolly, chubby, black-haired bundle of energy. When we first met, his eyebrows registered surprise when he saw me. I realized many years later that, to him, I must have looked like a child. At only 5-foot-2 inches, 110 pounds, with short, brown hair and freckles, I was wearing jeans, tennis shoes, and an old plaid flannel shirt, inherited from my big brother. But he recovered quickly and spoke so kindly to me that I immediately felt comfortable with him.

He looked at my concerned parents and grinned. “You don’t have to worry about anybody bothering your girl. The road to the lookout goes through Forest Service land and it has a locked gate. When you go up to see her, you’ll have to stop here for the key.”

Reassured, my parents hugged me and reluctantly left.

We loaded up my gear into his pickup, along with three large milk cans of clean water. We took off into the wilds southeast of Bandon. We eventually went through the locked gate onto a narrow gravel road, and on through more miles of brush and woods, finally climbing steeply up to my first lookout station—the Bill Peak Lookout.

I was disappointed to see that it was just a cabin sitting on top of the bare knob called “Bill’s Butte.” I was expecting a tower. But the rock knob projected so high above the surrounding territory, that a tower wasn’t needed.

My one room aerie was an old building with glass walls, starting about 2 feet from the floor. Below the windows, the walls were lined with wood benches, the tops of which were hinged to reveal storage underneath. Against the north wall was a small, wood range, used for cooking and heating. Against the east wall stood a metal cot, with a thin mattress. In the southwest corner my short-wave radio rested on a stand, with the forms I used to write down the locations of the smokes I would turn in. The cabin was finished out with a chair at the radio stand, a small table placed in the corner where the built-in benches met, and a kerosene lantern for light. There was no electricity.

Bill helped me haul in my gear, placing my three huge milk cans of clean water by the door. This was my drinking, bathing and cooking water. They would return regularly every week or so to bring me more. He pointed out my water bucket and basin, on a stand next to the stove, then the wood pile, chopping block, and axe located a few feet from the door. Making sure I had everything I needed, he checked the shortwave, turning it on to a loud wave of static and signed us on to the network. This static would be my incessant companion during all the hours I was signed on every day. I eventually got to where I could tune it out.

Bill issued last minute instructions. “If you have a problem, or need something, give us a call. Let us know if you run low on water. This should last you a week, so don’t waste it. I guess you noticed your outhouse as we drove by? Across the road?”

I nodded, cringing inwardly at the sight of the dirty old building.

“The silence enveloped me. The only sound was the wind in the trees below, and the blare of the radio.”

—Theresa Verboort

“Well, it looks like you’re all set. If you have any problems, don’t hesitate to call on the radio. We’ll see you in a week or two.” With that, he hopped into his truck and headed back down the hillside. I stood and listened to the truck spin through the gravel, the sounds growing ever more faint as it went on down and back to civilization.

The silence enveloped me. The only sound was the wind in the trees below, and the blare of the radio. Spot whined and began exploring his surroundings, sniffing at everything. Well, I wasn’t totally alone. I felt elated and frightened, all at the same time, as I took stock of my surroundings. Walking the narrow path around the building, I realized that I had a magnificent view to the south, north, and west. The west ended at the blue strip of ocean, far in the distance. To the east, my view was eventually blocked by the bulk of the coast range mountains.

I entered my new home and checked out the fire finder. I looked for landmarks to familiarize myself with the territory. I was assailed by doubts about my ability to use it correctly. To calm my nerves, I started setting up housekeeping. My food and clothes went into the storage benches. I set my battery powered radio on the table beside my cot, along with my travel clock. Books were stacked wherever there was a space to pile them. The small rug, Spot’s bed, was placed by my cot. I wasn’t about to have a dog in bed with me. My sleeping bag was unfurled on the cot, the pillow placed on top.

Nature called and I looked with trepidation at the outhouse, about 30 yards down the road from the cabin. I called Spot and we walked down and peeked in the door. It was festooned with spider webs and dust inside. What was I going to do? I considered my options, and, eventually, in desperation, grabbed the broom and a roll of toilet paper and marched back down to it. Holding my breath, I swept furiously until it was as clean as I could possibly get it. After that, using it became part of the routine.

I was isolated miles from anywhere except for the battery-operated shortwave radio that served as communication between me and the Forest Service. We lookouts all signed on in the morning at about six o’clock and left the radio on all day until we signed off at night. Every hour, while we were on the air, the dispatcher checked in with all the lookouts to be sure all was well. If someone didn’t answer, they checked back every 15 minutes until the person responded. After three checks with no answer, a ranger was sent to find out what was wrong. If we were going to be out of earshot we had to call in and let the dispatcher know, and for how long.

I “bathed” using the water bucket and washbasin in my cabin. The small, rusty old cook stove, for which I had to cut wood, was a source of concern. This was also my source of heat. When I baked in the oven, flakes of rust would drift down on the food. I could watch the flames through a couple of small holes rusted through the side of the firebox. I thought it would be ironic if the cabin burned down because of this ancient appliance.

When darkness descended, I lighted the kerosene lamp. My batter powered radio brought me music in the evening. During the day, I received mostly static on it, but at night I was getting stations from great distances, California, Arizona, who knows where else. I was able to bring in human voices and popular music. It was a comfort.

With my rifle and my dog for protection, I felt very grown up and self-reliant. And I loved having my own space for the first time in my life.

“I was in my own little world,

protecting my beloved forests.”

—Theresa Verboort

The Forest Service made sure there was a pile of stove wood for me to use. I was used to chopping wood at home, and enjoyed slicing the big chunks into smaller pieces to go in my stove. So, wielding the axe, and walks down the gravel road in the evenings with Spot in tow, helped stave off feeling confined.

My first summer passed uneventfully. I never tired of the view. And I got lots of reading done. And, after calling in my first smoke or two, I gained confidence in my ability to find them on the map. Over the summer, I turned in over a hundred smokes, most of which turned out to be people illegally burning trash. By the end of summer, I suspected the Forest Service personnel were tired of hearing from me. However, they knew that I was accurate and always checked my reports. Sometimes the fire would have been extinguished by the time they got there, but they always found it.

Only once was I concerned about a fire that got out of hand. A field burn got out of bounds, and I was smoked in for a couple of days before they got it out. The smell of smoke clung to everything in the cabin. Throughout the summer, the tension mounted as the dry season sucked the moisture out of the area and the fire danger increased.

I read to my heart’s content. My parents came up once a week or so, bringing me fresh reading material. I was on good terms with the town librarian, so she had a good idea what to send to me, classics as well as new books.

My parents also brought up my weekly supply of fresh groceries and on a couple of occasions, left behind one of my younger siblings to keep me company. At first, they would be excited to be “camping out” with their big sis. But after a day or two, they realized that it was boring for them. We would play checkers and board games, and, after sign off, go for walks. They also brought their own reading materials. Another favorite activity was baking biscuits, cake, and cookies in the rusty oven. But by the time the week was over, they were more than ready to go back home.

It was nice to have my sibling’s companionship, but I enjoyed being alone too. It was lovely to have my very own kingdom up there, above the trees. The days were busy, and the nights were peaceful as I lay on my cot, listening to far away stations. As time went by, however, and the fire danger mounted, I was on edge all day and relieved when the fog rolled in over the landscape at night to obscure my view. By the time I left in the middle of September, it was with great relief that I went on to my freshman year at college.

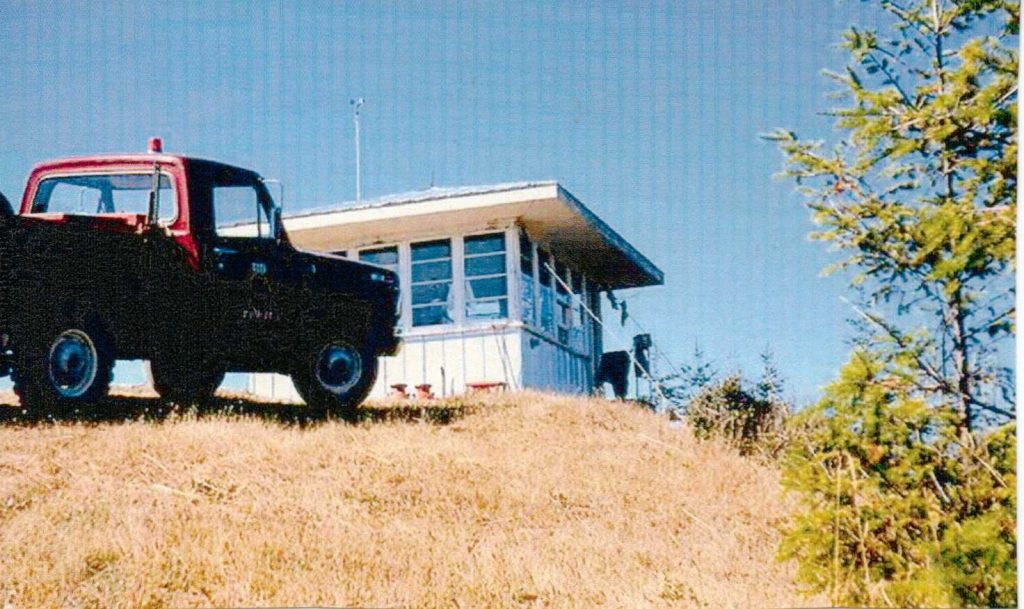

The next summer, 1959, I was stationed in a brand-new lookout on top of Beaver Hill, south of Coos Bay. It stood in a clearing next to a well-traveled county road. Five flights up, the cabin was basically the same as my last, but brand new. It was surrounded by a 3-foot-wide deck, with a trap door over the stairway. When the trap door was down and locked, no one could come up on top. Or so I thought.

To my delight, it had electricity. I had plenty of light to read by at night, and a new electric range for cooking. The downside was, the “outhouse” was five flights below. Yes, no plumbing. So, I had to carry my water up all those flights of stairs.

I eventually spent two summers as a lookout on Beaver Hill.

***

I enjoyed working as a fire lookout very much. Being a lookout was like being on a long retreat. I was in my own little world, protecting my beloved forests. The views were spectacular and I spent a lot of time reading and thinking. It was an opportunity to slow down and contemplate life in general. Those days will forever resonate in my memories, and have given me a lifelong love of and concern for our beautiful forestlands.

—Theresa Verboort

History & Architecture of Lookout Towers

Both of the towers Verboort worked at are no longer in service and were dismantled or destroyed. To learn more about historic and current lookouts, visit the Forest Fire Lookout Association, an organization that promotes the protection, enjoyment, and understanding of lookouts.

The Former Fire Lookout Sites Register has information about specific historic lookouts:

Bill Peak Lookout

Bill Peak’s L-4 cab, “by far the most popular live-in lookout,” according to the Forest Fire Lookout Association, was built by the CCC in 1938. L-4 architecture featured a 14×14-foot wood frame cab, windows all around, a four-sided hip roof, and ceiling joists to hold the window shutters open. Bill Peak Lookout was replaced by an Amort cab in 1962, which was removed in 1967.

Beaver Hill Lookout

In 1934, a 50-foot-tall wooden tower was constructed on Beaver Hill, south of Coos Bay. An Aircraft Warning System (AWS) cabin was added in 1942. In 1958, a 40-foot wooden live-in tower was built to replace these. The lookout was destroyed in 1962 during the infamous and destructive Columbus Day storm.

The Communing Tree: A book set amid wilderness

Theresa Verboort’s experiences and love of the wilderness areas inspired her to write her award-winning novel, The Communing Tree. The story takes place in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness of southern Oregon. Judith, 16, and her sister, Kali, age 5, find themselves left alone in a cabin in the wilderness. Their survivalist parents and older brother have been murdered, and the girls escape to their hidden cabin in the wilderness where their grandmother is caring for the place. Kali, because of the shock, is mute. The story of their struggles to survive after their grandmother passes and the appearance of a mysterious stranger who becomes their friend keeps readers enthralled to the end. The book is available on Amazon.

To read about another adventure (or in this case, a misadventure) in the wilderness, read Lost on Lawson Creek by Gail Oberst.

Mountain Lookout is a web-exclusive story originally published in Oregon Coast magazine online on July 18, 2022. The story is copyrighted under First North American Serial Rights and may not be used without permission.